By: Amnon Ben-Tor, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Edited and abridged from NEA 76.2: 66–67 (see editorial note below)

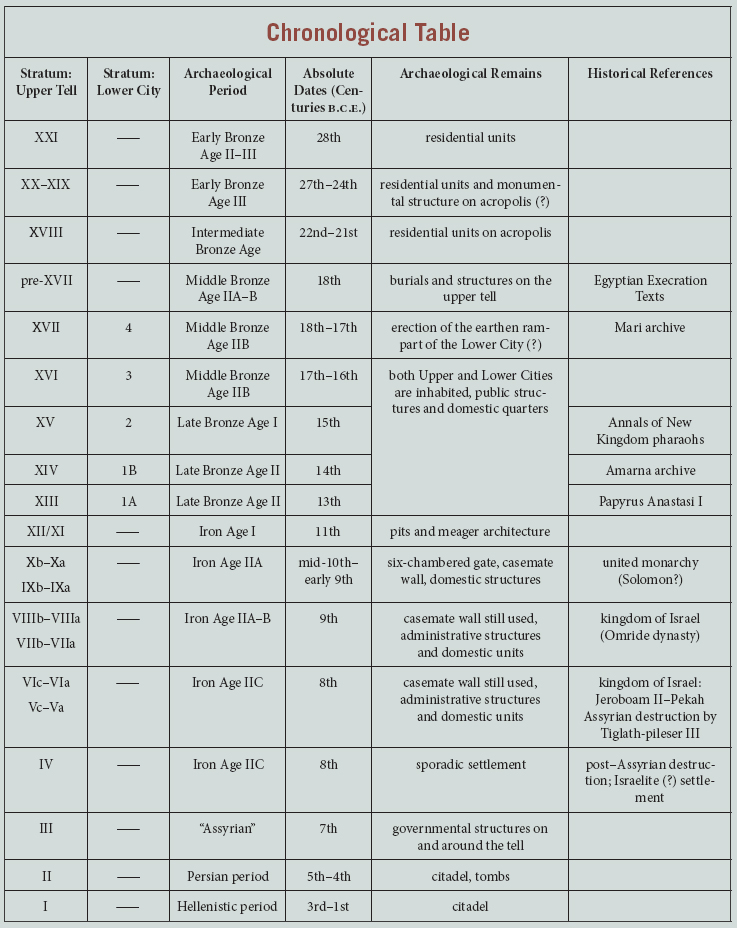

Tel Hazor, “the head of all those kingdoms” (Joshua 11:10), is the largest tell in Israel and encompasses a total of approximately 800 dunams (200 acres). With the exception of two gaps in the settlement, one at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age and the other following the destruction of the Canaanite city during the transition between the Late Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, Hazor was continuously occupied for approximately two millennia, from the first half of the third millennium BCE to the late eighth century BCE.

Tel Hazor, “the head of all those kingdoms” (Joshua 11:10), is the largest tell in Israel and encompasses a total of approximately 800 dunams (200 acres). With the exception of two gaps in the settlement, one at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age and the other following the destruction of the Canaanite city during the transition between the Late Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, Hazor was continuously occupied for approximately two millennia, from the first half of the third millennium BCE to the late eighth century BCE.

Following the Assyrian conquest of Hazor in the year 732 BCE along with several other important sites in the region (as referenced in 2 Kgs 15:29), a period of decline set in until the site was finally deserted. A short-lived Israelite (?) settlement (Stratum IV) was established on top of the ruins of the fortified Israelite city. Poor traces of occupation attributable to the Assyrian, Persian, Hellenistic, and Islamic periods (Strata III–0, respectively) were noted at different locations on Hazor’s acropolis.

In the 1950s and 1960s, extensive excavations were carried out by Professor Yigael Yadin in two parts of the site: the Upper City (the “acropolis”) and the Lower City (the “enclosure”). The excavations, conducted on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, were the largest conducted at any site in Israel at the time. Hazor’s selection for excavation was no doubt due to the biblical accounts in the books of Joshua and Judges of the settlement of Israelite tribes in Canaan.

According to this narrative, Hazor was the site of a decisive battle, as a result of which “Joshua took all that land: the hill country and all the Negeb and all the land of Goshen and the lowland and the Arabah and the hill country of Israel and its lowland, from Mount Halak, which rises toward Seir, as far as Baal-gad in the valley of Lebanon below Mount Hermon” (Joshua 11:16–17). The book of Judges presents a different version: “So the Lord sold them into the hand of King Jabin of Canaan, who reigned in Hazor; the commander of his army was Sisera, who lived in Harosheth-ha-goiim. … So on that day God subdued King Jabin of Canaan before the Israelites. Then the hand of the Israelites bore harder and harder on King Jabin of Canaan, until they destroyed King Jabin of Canaan” (Judges 4:2, 23–24).

From the outset, the early excavators of Hazor disagreed regarding the credibility of these accounts and which of the two was a description of what had actually taken place. Yadin and Aharoni were the main protagonists: Yadin’s position, following William F. Albright, was that the narrative in the book of Joshua was more trustworthy than the version in the book of Judges, which Yohanan Aharoni, following Albrecht Alt and Martin Noth, preferred.

Yadin and Aharoni, faculty members of the Department of Archaeology at the Hebrew University, were the chief directors of the excavations. Joining them as area directors were Claire Epstein, Trude Dothan, Moshe Dothan, Ruth Amiran, Jean Perrot, and others. Immanuel Dunayevsky served as the chief architect.

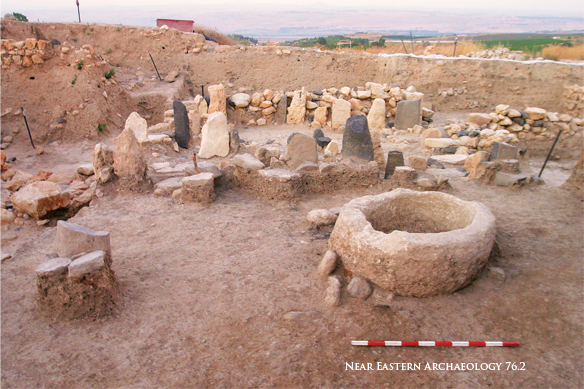

Iron Age buildings dating to the tenth century BCE excavated below the famous “Pillared Building” on the Upper City.

It would be no exaggeration to say that these archaeologists were the “founding fathers” of biblical archaeology in Israel who taught excavation methods to generations of future archaeologists. Dunayevsky established new surveying and registration methods that, even after more than fifty years, are still in use today by archaeologists working at biblical sites. During the five seasons of excavations by the Yadin expedition (1955–1958, 1968), many students from the Hebrew University (the only university in Israel at that time) participated alongside a technical staff of surveyors, draftspersons, photographers, and others. The site of Hazor, in fact, served as the main school for teaching “field archaeology,” and many of its graduates have since then taught archaeology at universities in Israel and around the world or were employed by government institutions such as the Israel Antiquities Authority and various museums, where they passed on the “Israeli tradition” from one generation of archaeologists to another. Today students at the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University are the fourth (!) generation receiving their initial training in field archaeology at Hazor.

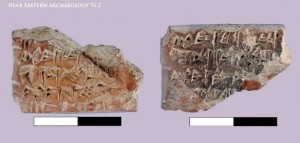

Fragments of Middle Bronze Age cuneiform tablets written in Akkadian containing laws similar to the famous Code of Hammurabi.

The excavations of the Yadin expedition uncovered a rich and varied assortment of large finds, including fortifications, temples, dwellings, and water systems, and a wide variety of small finds, such as local and imported pottery, weapons, numerous art objects, statues of dignitaries and deities, cuneiform documents, and the like. These finds attest to the city’s importance and to the significant role it played in the economic and political scene in the ancient Near East, in both the neighboring regions and in far-off lands. The excavation results aroused great interest among scholars in many fields: historians, biblical scholars, specialists in ancient art and religion, and other diverse fields.

Some accepted the expedition’s conclusions; others challenged them. In the center of the controversy stood, and still stands, the Yadin expedition’s conclusions concerning the biblical narratives that refer to Hazor, especially the questions of the conquest and settlement of the Land of Israel (Joshua 11:10–17) and the attribution of the construction of Hazor’s fortifications (dated by Yadin to the tenth century BCE) to Solomon (1 Kings 9:15). Both the Yadin expedition and the current excavations established that the number of Iron Age strata dating from the eleventh century to the last third of the eighth century BCE (seven strata divided into numerous substrata) exceeds the number of contemporary strata discovered at any other site in Israel. It is, therefore, not surprising that Hazor stands at the forefront of the ongoing controversy over the reliability of biblical historiography. Despite the vast area explored by Yadin’s excavations and the immense contribution the resulting data gave to the study of the history of the southern Levant and neighboring countries, the excavations left many questions unanswered and others with unsatisfactory answers. Some of the conclusions reached by the Yadin excavations remain open to dispute, and they are tackled by members of the renewed excavations.

Editorial note: The Ancient Near East Today is pleased to feature several edited and abridged versions of articles on the renewed excavations at Hazor that are published by ASOR in the journal Near Eastern Archaeology 76.2. The above essay by Prof. Ben-Tor serves as an introduction to the issue. An abridged version is reproduced here together with a gallery of illustrations that give a flavor of what is found in whole issue. In July, August, and September, ANE Today will feature articles treating the Canaanite City (July), the United Monarchy (August), and the 8th and 9th centuries (September). Each essay will be accompanied by illustrations that demonstrate how important Hazor is to our understanding of the biblical world and the region in general.

Do you want read to these articles on Tel Hazor in their entirety? We are offering 30 days of free access to this issue of Near Eastern Archaeology! All you have to do is follow this link to sign up for free access through JSTOR: ! (If you already have a myJSTOR account, sign in before you click the link). As an added bonus, if you are not already a Friend of ASOR, we will register you as a Friend so that you receive The Ancient Near East Today each month for free.

Gallery of selected images from NEA 76.2—Issue on Hazor:

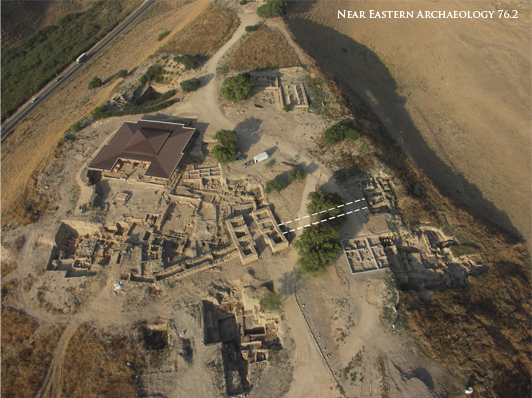

Aerial view of public buildings in the center of the Upper City at Hazor showing Middle Bronze Age remains including (1) the early palace (the roofed building covers the Late Bronze Age Ceremonial Palace (or temple), (2) the Southern Temple, (3) the maṣṣebot complex, and (4) subterranean storehouses. The Iron Age “Solomonic Gate” is on the lower right of the photo.

The Middle Bronze Age maṣṣebot complex near the Southern Temple. During the Late Bronze Age the area was covered and became an open courtyard.

Fragments of Middle Bronze Age cuneiform tablets written in Akkadian containing laws similar to the famous Code of Hammurabi.

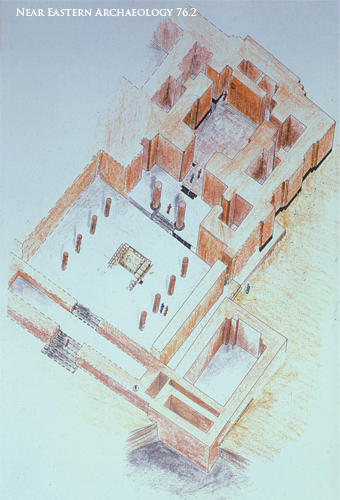

Reconstruction of the Late Bronze Age Ceremonial Palace showing the courtyard, porch and central room. The excavators continue to debate whether the structure is a palace or temple.

Iron Age buildings dating to the tenth century BCE excavated below the famous “Pillared Building” on the Upper City.

Aerial view of Iron Age structures from the ninth century BCE with the public storehouse at the center.

If you liked this article please sign up to receive The Ancient Near East Today via email! It’s our FREE monthly email newsletter. The articles will be delivered straight to your inbox, along with links to news, discoveries, and resources about the Ancient Near East. Just go here to sign up.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

There was also an occupation gap between the Iron I and Iron IIa settlements.

Pingback: JuneBiblical Studies Carnival | The Blog of the Twelve