By: George Athas

Summer[1] is an exciting time, and not just because of the weather. It’s the time the archaeological fraternity dusts off its trowels and spades and sets to work digging the tels. Hopefully there are cohorts of grad students to do most of the dirty work. And hopefully, one of them will stumble upon an inscription or two: an ostracon with faint traces of inked letters, a bowl fragment with incised figures, or perhaps even a stone block with hard-chiselled text. Each new inscriptional find brings another fragment of the past into our own time. Piece by piece, our construction of Biblical history becomes more solid.

I’m not the only one who feels a little rush whenever we make such a find. I’m sure most of the ASOR constituency experiences the same palpitations, and the last few seasons have fortunately yielded several such finds. One of these was the Bethlehem bulla found in excavations at the City of David during.

I must admit that I was sceptical about reading ‘Bethlehem’ on this little find when I first saw photos of it, and said so on my blog. I initially thought the letters in question should be read bt lh or “daughter of Lah[…]! But I also managed to prove a cardinal rule on which I insist with inscriptions: no matter how good the photos and drawings of an inscription might be, nothing is better than a personal inspection. After a few pairs of trained eyes examined the bulla, it was confirmed that the bulla did indeed read ‘Bethlehem’. The exciting thing about this is that it is a non-Biblical source that shows Bethlehem may have been an important administrative centre in the kingdom of Judah.

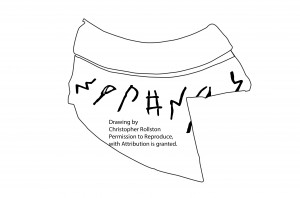

Another discovery making the headlines this year was the tenth century bce inscribed pithos fragment from the Ophel in Jerusalem. With precious few letters to go by, the text was inherently ambiguous – it appears to be just a string of letters rather than a clear name- compounded by the fact that some of the forms were difficult to determine. Then there was the direction of the writing, right to left or left to right? In the formal publication of the object excavator Eilat Mazar and epigrapher Shmuel Ahituv announced the inscription was a proto-Canaanite sinistrograde text, that is, from right to left.[2]

Eilat Mazar holding the pithos jar rim with inscription.

Drawing of the pithos rim by Chris Rollston.

But from this Mazar claimed the text confirmed that King David used Jebusite administrative personnel in Jerusalem. While I would love Mazar to be correct, I fear the claim is more wishful thinking than reasoned conclusion, not least because their proposed text was unintelligible. What can be said is that, as with earlier and still enigmatic finds from Khirbet Qeiyafa, which the excavators’ have been argued to be Hebrew, new inscriptions are showing us higher levels of organisation, administration, and modest literacy within Israel and Judah, even at the beginning of Iron II.

One of the scholarly dangers in our field is letting the excitement of an inscriptional find take us down avenues where we want to go, rather than having a more restrained approach. Part of the problem with this is, as many archaeologists and historians have found in recent years, the news media are prone to sensationalizing finds when they bear upon ‘biblical’ times without our coaxing. The result is the dissemination of misinformation. And news certainly travels quickly these days.

Tel Dan Inscription

Eric Cline of George Washington University has written an important essay on the interaction between our field and the media, and I commend his thoughts and suggestions.[3] In addition, I want to propose three things that we could be doing as archaeologists, epigraphers, and historians. First, when announcing new finds (and not just inscriptions), we should stress the provisionality of our initial conclusions. That is, no matter how convinced we are of our own deductions, we should avoid setting them in concrete. We should get into the habit of making preliminary conclusions, and then be willing to budge as discussion proceeds. Scholarship is a conversation, not a decree.

This leads to my second point: we should be inviting analysis and discussion from others in the field. We need to foster interaction between experts in the various disciplines, and do this in a deliberate way for the news media (not to mention our students) to see. The general public is quick to jump on a big claim when it comes to ‘biblical’ finds, so we need to say loudly that determining the significance of an inscription is a complicated matter. In particular, we should be willing to wait for fuller understanding of archaeological contexts in which finds are made. This usually takes a few more seasons of excavation, so patience is a key virtue.

And third, we need to be more measured in the conclusions we put forward. Interpreting finds is as much an art as it is a science, but there are still logical guidelines to follow. Let’s not go turning a ‘button’ into a whole ‘suit’. There might be pressure on excavators to come up with particular results, but we must interpret finds judiciously, noting the difference between possibility and probability. I think this will be aided if we foster a collegial approach to analysis.

Discussion on the inscribed pithos from the Ophel is a case in point. After the initial media coverage, thoughtful discussion on blogs and social media about the meaning and significance of the inscription got underway. Some important new ways of looking at the inscription were raised, including from Christopher Rollston[4] (who has proposed the inscription consists of the words for “pot” and the name “Ner”!) and Gershon Galil.[5] And I don’t think discussion is at an end either. With these new outlets for conversation, the world has become a much smaller place. This should make collegiality in our field easier. We just need the will to pursue it. In turn, this will increase public appreciation about how scholarship is done and what new finds might really be about.

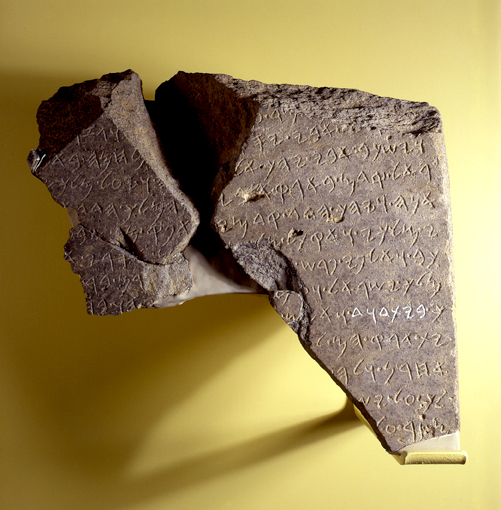

Tel Dan Inscription

Finding room to display important finds in museums is a constant challenge. But there are two other challenges that museums face: how to display such finds, and what to do with unprovenanced finds. On the first point, I was disappointed to learn that the Israel Museum is now displaying the Tel Dan Inscription with plaster covering the supposed join between the fragment clusters, and without a clear view of the rear of the fragments. This is inappropriate and wrong.

Over a decade ago I questioned the configuration of the fragments as they are currently displayed. Part of the argument was that the two fragment clusters do not actually join. I still stand by my analysis, but the relevant area is now totally hidden from view, precluding any further analysis. One saving grace is that the text is still clearly visible. This should allow epigraphers to observe the extra letter that is unfortunately masked in the photographs and drawings, but which still protrudes above the lacuna on line 4 (Fragment A). This extra letter (a lamed) changes the meaning of the much touted text and, in my opinion, scuttles the current display configuration. In any case, displays should foster further transparent study of object and their complexity, not cover them up.

Gihon Spring Inscription.

On the authenticity front, unprovenanced finds are a constant challenge. I do not want to sideline them completely; we might be ruling out good evidence. We do not need to take the kind of approach to this potential evidence that judicial systems take to evidence obtained without a relevant search warrant—that it is inadmissible. We are not engaged in a legal endeavour, but an historical one. But nor do I wish to encourage private acquisition of such finds outside of controlled environments. Curators need to make a call about whether to display such finds (mostly bullae), but they certainly should make them available for study. If museums do display such finds, then labelling them as unprovenanced is a must. Of course, there is also the ugly spectre of the forgery (something not limited to bullae). As far as I can see, the most effective weapon against the forger is not the legal system, but the skilled epigrapher. The ever-present possibility of forgeries shows the great need to conduct controlled environments at relevant sites.

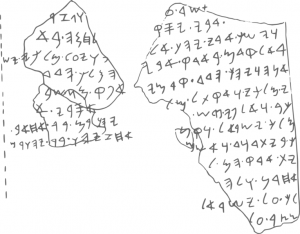

Khirbet Qeiyaga Inscription.

It is exciting to see what we already have and to imagine what lies ahead. Most excitingly, more inscriptions have appeared bearing names similar to those found in the Bible. In, in addition to the inscribed pithos fragment, an inscribed ceramic bowl bearing a name […]ryahu ben Benaya, similar to the Biblical prophet Zechariah ben Benaya (father of the biblical prophet Jahaziel [2 Chronicles 20:14]), and dating to the seventh century bce was also uncovered near the Gihon Spring at the City of David excavations. Our picture of the region during the Iron Age is becoming sharper, ‘pixel by pixel’, especially in the very heart of Jerusalem itself. Hopefully further inscriptional finds in years to come might help us join a few more dots about the makers of these inscriptions.

George Athas is Dean of Research at Moore Theological College in Sydney, Australia.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

[1] I am, of course, talking about summer in the northern hemisphere. In Australia, where I live, it’s the dead of winter!

[2] E. Mazar, D. Ben-Shlomo, and S. Ahituv, ‘An Inscribed Pithos From the Ophel, Jerusalem, IEJ 63/1: 39–49.

[3] Eric H. Cline, ‘Fabulous Finds or Fantastic Forgeries? The Distortion of Archaeology by the Media and Pseudoarchaeologists, and What We Can Do About It’, in Archaeology, Bible, Politics, and the Media: Proceedings of the Duke University Conference, April 23–24 (ed by. Eric M. Meyers and Carol M. Meyers; Winona Lake, IA: Eisenbrauns), 39–50.

the picture stating "Khirbet Qieyafa inscription" is, of course Tel Dan inscription - as can be seen a drawing of it a little down the article…

The "Dan/House of David Inscription" is labeled as the Qeiyafa Inscription. Actually, check the labeling of all the inscriptions—several are off the mark.

Photos of inscriptions are mostly mislabeled here. Someone at ASOR has to be able to fix that!

Nice article. I just wanted to point out that a few of these pictures are incorrectly labeled.

I think that the labels have been fixed now. Thanks to the readers who noticed the mistakes.

Not yet. Well, the pictures may be labelled correctly but they link all over the place.

Pingback: George Athas on Discoveries of Ancient Inscriptions in Israel and the Bible