By: C.D. Elledge with Olivia Yeo

Who really wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls? Twenty years ago, the available options for understanding the identity of the Dead Sea Scrolls Community were relatively concise. Consensus associated the origins of the community with the ascetic Essenes. A few dissenting opinions highlighted its commonalities with the priestly Sadducees or associated the Scrolls with Jerusalem refugees who fled into the wilderness during the Great Jewish Revolt (66-70 CE).[1] A frequent assumption is that the manuscripts somehow represented the collected religious literature of a single community. Qumran excavator Father Roland De Vaux’s archaeological interpretation of the site further linked the site with the nearby caves in which the Scrolls were found, situating this movement’s activities in the wilderness to the early Hasmonean era, sometime after ca. 140 BCE. [2] The picture seemed fairly clear.

Aerial view of the Qumran community.

Today, however, the picture is increasingly complex, thanks to two important factors. First, the full publication of the Scrolls has challenged current studies to account for the broad diversity of the literature, as well as the complex editorial and literary histories of individual writings. The underlying historical and social dynamics of the community that shaped this literature in all its various editorial forms remains an ongoing problem.

Living quarters at Qumran.

Second, while defending a sectarian interpretation of Qumran, Jodi Magness’s later dating of its Hellenistic occupation at the site to the first half of the first century BCE[3] has increased the need to consider the late Hasmonean era as the crucial setting for the community’s ongoing religious ideology and polemics. Moreover, this later dating has also raised increasing questions about the extended “pre-history” of the “parent-movement” that preceded at Qumran.

Two recent approaches highlight important attempts to account for a broader range of textual evidence, as well as a later sectarian occupation at Qumran.

Enochic Origins

One recent theory about the earlier parent-movement that inspired the Dead Sea Scrolls community is that of Enochic origins. Scholarship has often regarded the book of 1 Enoch (which was not included in the Tanakh) as the textual expression of an estranged Jewish community that rejected the competing narrative of Judaism promoted by the post-Exilic editors of the Torah. Enochic Judaism consisted of a unique ideology with a distinctive interpretation of human origins (where fallen angels instruct humanity and create a race of giants), a deterministic understanding of theodicy, or the problem of evil, and a veneration of Enoch (Noah’s great-grandfather) as the unparalleled vehicle of divine revelation.[4]

University of Michigan Enoch specialist Gabriele Boccaccini argues that among the proliferation of Jewish sects in the early Hasmonean era, it was the Essenes, in particular, that carried this earlier Enochic heritage. The more specialized religious sect at Qumran represented a radicalized outgrowth of this earlier Enochic-Essene movement, one created by a schism over the authoritative claims of the “Teacher of Righteousness.”[5] This concept allows Boccaccini to distinguish the literary remains of the earlier Enochic parent-movement (which included biblical texts, portions of 1 Enoch like the Book of Watchers, Dead Sea Scrolls like the Temple Scroll, Jubilees, 4QMMT) from those shaped by the emerging schism (e.g., the famous Damascus Document) and its Qumran-sectarian aftermath (e.g., Rule of the Community, Pesharim). The sectarians in the settlement at Qumran in the early first century BCE did not represent the proud headquarters of the larger movement, but rather an increasingly alienated and irrelevant offspring.

Other scholars, however, have criticized the assumptions Boccaccini uses to constructs his conclusions. John J. Collins of Yale Divinity School, for example, questions the relationships drawn between Essenes and Enochic literature: “It seems to me unjustifiable to apply the label ‘Essene’ to the Enochic Books or even Jubilees, which contain no description of community life.”[6] We may also ask why the sectarian rule-books, like the Rule of the Community and the Damascus Document, make no mention of Enoch as an authoritative figure; they simply ascribe authority to the Torah. [7]

A Variegated Sectarian Movement

Collins has also reconsidered the identity of the Dead Sea Scroll community, returning especially to an analysis of the major rule books and their literary history. In Beyond the Qumran Community (Eerdmans), he argues that the two sets of rules do not reflect a schism or different chronological stages within a single entity but rather existed side-by-side within a socially varied religious movement.[8] The “new covenant” of the Damascus Document reflects the broader character of the movement. Its covenanters consisted of marrying households that, nevertheless, organized into a larger community structure. The covenant made stringent demands that superseded traditional patriarchal norms, without otherwise requiring complete isolation from society.

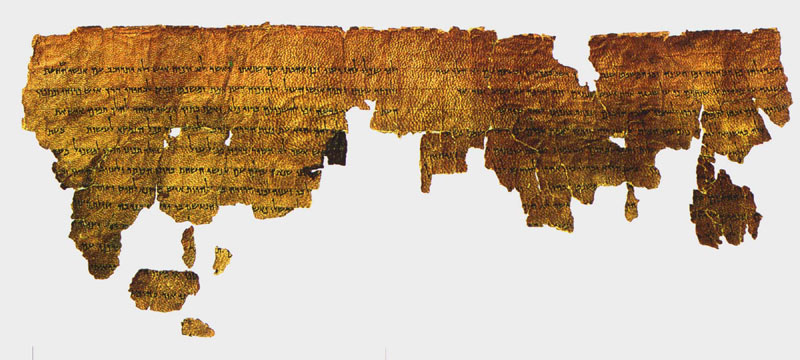

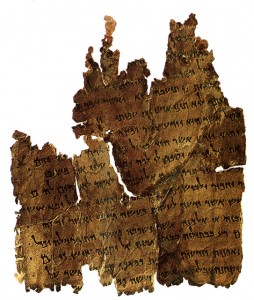

The Rule of the Community Scroll.

Alongside the Damascus covenant, there is the more specialized group called the yahad of the Rule of the Community. This group, dedicated to “perfect holiness,” was not a single congregation but a collective made up of smaller communal cells that took up “multiple places of residence.”[9] As for the relationships of the yahad to Qumran, Collins suggests “the Scrolls should not be tied too closely to that of the site. At most, Qumran was one settlement of the yahad. It was never the yahad in its entirety.”[10] Historically, Collins situates the Teacher of Righteousness within the first half of the first century BCE. His conflicts with the Wicked Priest may only have been a series of episodes at the end of his career. In this view the original impetus for the Dead Sea Scrolls community originated in conflicts with the Pharisees over Jewish law, not in turmoil with Jerusalem’s priesthood.

Collins regards the rule literature as concurrent, yielding a portrait of the varied forms in which the Dead Sea Scrolls community lived out its religious ideology. Perhaps the most promising implication of Collins’ approach is that it may provide a model of communal life that accounts for the diversity of the Scrolls themselves and even the variant editions of major sectarian works within the collection. One may, for example, imagine different cells within the yahad producing variant editions of the same sectarian literature, according to their own more immediate needs.

Future Horizons

From the beginning of the discovery, scholars of the Dead Sea Scrolls community faced the challenges of limited and ambiguous evidence, as well as the uncertain relationships between the Scrolls and the archaeology of Qumran. Whether we are moving “Beyond the Essene Hypothesis” or “Beyond the Qumran Community,” the way forward will be paved with increasing complexity.

Among the many problems posed by the studies of Boccaccini and Collins, at least three will shape future studies. First is determining which texts within the larger Dead Sea Scrolls collection provide evidence for the underlying community. Second, what are the implications of shifting the focus for Qumran origins from the earlier Hasmonean age to a later Hasmonean setting? And third, even among those scholars who associate Qumran with the Dead Sea Scrolls community, how to we determine the precise character of that relationship? Was it a sectarian headquarter, home to a radical offshoot, or one settlement of the yahad? These questions will proliferate in the future.

C.D. Elledge is Associate Professor of Religion, Gustavus Adolphus College; Olivia Yeo is a student researcher in English and Religion.

If you liked this article please sign up to receive The Ancient Near East Today via email! It’s our FREE monthly email newsletter. The articles will be delivered straight to your inbox, along with links to news, discoveries, and resources about the Ancient Near East. Just go here to sign up.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

[1] A summation reflective of this situation may be found in James C. VanderKam, The Dead Sea Scrolls Today (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1994), 92-98.

[2] Roland de Vaux, Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls (Schweich Lecture, 1959; London: Oxford University Press, 1973), 1-44.

[3] Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls (SDSSRL; Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans), 60-71.

[4] Gabriele Boccaccini, Beyond the Essene Hypothesis (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1998), 170-178; Boccaccini, ed., Enoch and Qumran Origins: New Light on a Forgotten Connection (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans); “Enochians, Urban Essenes, Qumranites: Three Social Groups, One Intellectual Movement,” in The Early Enoch Literature (ed. J. Collins and G. Boccaccini; JSJSup 121; Leiden: Brill), 301-327.Boccaccini, Beyond the Essene Hypothesis, 170-178.

[5] Boccaccini, Beyond the Essene Hypothesis, 186-192.

[6] John J. Collins, “ ‘Enochic Judaism’ and the Sect of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in The Early Enoch Literature, 294.

[7] More recently, Boccaccini has made some minor qualifications of his hypothesis: The Qumran movement may represent a split from the Urban Essenes, who carried on the Enochic heritage, rather than directly from the larger Enochic movement itself. See his, “Enochians, Urban Essenes, Qumranites: Three Social Groups, One Intellectual Movement,” in The Early Enoch Literature, 301-327.

[8] John J. Collins, Beyond the Qumran Community: The Sectarian Movement of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans).

[9] Collins, Beyond the Qumran Community, 69.

[10] Collins, Beyond the Qumran Community, 208.

Pingback: Biblical Studies Carnival XCIV: December| Cruciform Theology