By: Suzanne Richard, Professor

Department of History and Archaeology; Department of Theology Director,

The Collins Institute for Archaeological Research and the Archaeology Museum Gallery at Gannon

Calamity, upheaval, and dislocation, whether wrought by human disasters such as war or natural agents such as earthquake and climate change, eventually face all societies. But in an era of ever greater urbanization and environmental uncertainly are there lessons to be learned from ancient societies that contended with dramatic changes? The Early Bronze IV (EB IV) Period (ca. 2500–2000 BCE) is one such example and offers a fascinating look at how people survived the dramatic collapse of urban life.

Map of EB IV sites showing location of Khibet Iskandar on the Wadi Wala. All images courtesy of Suzanne Richard unless otherwise noted.

The EB IV saw an abrupt transition from urban to rural life in the face of destruction and abandonment of tells/sites by the end of EB III. What follows is a period (called alternately EB IV/EB–MB/Intermediate Bronze Age) that has been mired in scholarly controversy for half a century: Is it a “dark age,” a “pastoral-nomadic” interlude, or an “intermediate” period cut off from the preceding and succeeding (Middle Bronze Age) urban periods? Or, is it really just a period of permanent agricultural settlements continuing an age-old tradition of sedentism?

Some 50 years after the famed excavator of Jericho, Dame Kathleen Kenyon, popularized the “Intermediate” and “nomadic” perspectives, it is fair to say that we may finally have a grasp on the culture of the EB IV period. The picture is complex. Predictably, the answer lies somewhere in between. This period between urban eras is neither wholly pastoral nor wholly sedentary. Rather, it is a rural period with a variety of lifestyles along a continuum of sedentary and pastoral responses particular to specific regions.

For example, the site in the central Negev desert, Beer Resisim, is characterized by circular structures that suggest a community resident only part of the year; these pastoralists were ‘semi-sedentary.’ The discovery of copper ingots and objects also suggests tinkerers and trade between Beer Resisim and the mines to the east at Faynan in Jordan, which have been demonstrated to have provided copper to Egypt. Elsewhere, pastoralists occupying caves at Jebel Qa’aqir in the northern Negev seem to have tended flocks. These demonstrate the resilience of people as they shifted along a continuum from more settled to more pastoral subsistence strategies, in the face of change or adversity.

But at another end of the spectrum are permanent agricultural settlements, such as Khirbat Iskandar. Nine seasons of excavation directed by Suzanne Richard from Gannon University and co-directed by Jesse. C. Long, Jr. from Lubbock Christian University have concentrated on the EB III/IV periods. With three stratified phases of continuous EB IV occupation above a well-fortified EB III settlement, the site is a virtual laboratory for studying ancient survival strategies. The archaeological record illuminates the stages of recovery, growth, and stability in the EB IV [i].

Located on the Central Plateau in Jordan, the site is about a 20 minute bus ride from our hotel in Madaba, (complete with swimming pool!) south through the fabled Plains of Moab. Long gone are the early digs of living in tents near the site! About 25 kilometers east of the Dead Sea, as the crow flies, Khirbat Iskandar lies at a strategic crossing of the Wadi Wala on the King’s Highway. The latter was an ancient caravan route, popularly known from the biblical narrative of the Hebrews’ trek from Sinai to Mt. Nebo (Numbers 20:17; 21:22), and still the main north-south artery in Jordan today.

The level of the perennial water stream, the Wadi Wala, was a major factor allowing the existence of the site. It also provides an important lesson from the past. Warming trends in the climate can have both short effects, creating erratic water level in streams such as the Wadi Wala, and long-term ramifications during periods of sustained drought. The short-term impact on the site manifested itself in the reversion from urban to rural institutions in EB IV. The long-term impact saw the site’s abandonment at the end of EB IV, a condition that lasted until archaeologists arrived.

So, how can one infer ancient social processes such as recovery, growth, and stability from excavation of architecture and artifacts? At Khirbat Iskandar, we discovered three superimposed EB IV settlements at the southeast corner of the site. The lowest was a phase that included EB III as well as EB IV pottery. It appeared to reflect a period of recovery after the destruction of the site and fortifications in EB III.

Above this transitional phase was a residential settlement with well-made broadroom houses and a ceramic repertoire distinguished by classic EB IV pottery but that also clearly continued EB III tradition. This “hybrid” pottery suggests change, innovation, and growth in ceramic production. The new ceramic style emanates from contemporary Syria, a far more cosmopolitan society, and may indicate new elements in the population or just strong cultural influences that diffused from the north. Finally, the uppermost and latest, best preserved settlement is a unique EB IV gateway.

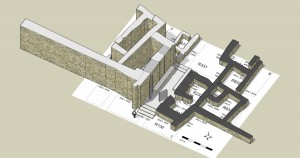

As shown in the photo and reconstruction, the gateway is plastered and lined with benches, and runs through a curtain wall built across the crest of the site. There are steps at both the lower and upper end and on either side are structures that perhaps were “guardrooms.” Later biblical texts refer to “elders at the gate” and “justice in the gate,” providing a possible window into activities in the EB IV gate at Khirbat Iskandar. Along with a storage area and top-loading bin, large stone platforms and significant flint debris suggest an industrial area to the east. Although the gate exemplifies a functional change from residential to public, the reuse of earlier walls and similar ceramics also point to continuity and stability.

Broader excavations at the northwest corner of the tell confirmed the site’s prosperity that balanced innovation, and earlier EB III traditions. For example, in our middle phase a public, multi-roomed building with storeroom came to light. It contained an enormous number of pots (150 whole vessels and counting!) and interesting array of cultic features including a stone-lined bin, pits with pottery and food remains and goat horn cores, and over 16 miniature vessels.

We believe that the data, including prestige items such as a unique bronze spearhead, zoomorphic figurine, and imports, indicate the presence of elites and a stratified society in residence at the site. When we consider the three cemetery areas nearby, along with standing stones, cultic buildings, and a “high place” on the hilltop behind the site (as well as reuse of fortifications), we have quite a well-established EB IV settlement surviving and indeed thriving in the face of adverse changes at the end of EB III. All this is a far cry from the purely nomadic EB IV that was assumed a few generations ago!

But what were the adverse changes at the end of EB III? Studies of geomorphology, pollen, and botanical remains suggest an explanation[ii]. While the fertile floodplain created by the Wadi Wala fostered the growth of the urban site during EB III, a probable combination of drier conditions and land overuse at the end of that period led to reduced agricultural potential by EB IV, and the destruction of the floodplain by the end of that period. Human activity intensified the effects of climate change and forced important changes, less dramatic at Khirbet Iskandar than elsewhere but significantly changing the character of the site nonetheless.

As we contemplate current global warming trends, Khirbet Iskandar’s narrative of EB IV survival – from recovery to growth and then stability – provides a glimmer of hope regarding human resilience. This narrative should also give one pause, as we note the ultimate triumph of nature and, in this case, abandonment of the site.

Suzanne Richard is Professor in the History and Archaeology Department, and director of the Collins Institute for Archaeological Research at Gannon University and the Archaeology Museum Gallery at Gannon.

[i] For a detailed report on the excavations see S. Richard, J.C. Long, Jr., P.S. Holdorf, & G. Peterman Khirbat Iskandar Final Report on the Early Bronze IV Area C “Gateway” and Cemeteries. Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar and its Environs, Jordan Vol. 1. Boston: The American Schools of Oriental Research.

[ii] C.E. Cordova, Millennial Landscape Change in Jordan: Geoarchaeology and Cultural Ecology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press: 189–91.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

Pingback: Suzanne Richard | Acor Jordan