By Dr. Jean Li, Ryerson University

Whenever I teach Ancient Egypt I begin by asking my students, “What comes to mind when you think about Ancient Egypt?” The replies, as one can imagine, invariably include “pyramids”, and “King Tut”. These are indeed our images of ancient Egypt: kings and great monuments to kings. Strikingly absent are narratives of women.

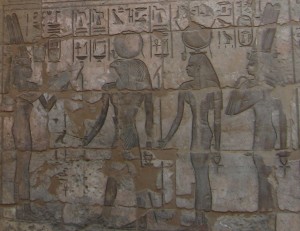

Ancient literary and artistic sources characterize ancient Egyptian women as wives, mothers, and daughters who derived their status and identities from associations with their male relatives. For most of Egyptian history women shared their husbands tombs’ as the subordinate companion. Three and two dimensional images depict women as devoted companions who kneel at the feet of their husbands or with a supportive arm draped around her husband, who strides forward with purpose. This normative value has resulted in a tendency to discuss women as one-dimensional subjects whose identities were defined by men.

In the last two decades, Egyptology has seen a number of studies published to add depth and dimension to discussions of women, and my research belongs to and builds upon this trend. My approach is archaeological and anthropological and examines, through material culture, the ways in which ancient Egyptian women actively participated in and transformed societal practices.

I use as my study the burial practices of elite women in Thebes in southern Egypt, in the 8th-6th century BCE. This was a period when Egypt was politically and socially fragmented, ruled over by a series of foreign powers that adopted Egyptian culture to the point that they seem more Egyptian than the Egyptians. This complex social and political environment created an environment of cultural innovation and archaism, which I suggest is indicative of a societal wide process of elucidating Egyptian identity. As contributing members of society, women, too, participated in this social dialogue. The women that constituted the most distinctive presence in the archaeological records were those who held the title of “The Singers in the Interior of the Temple of Amen.”

Members of this group seem to comprise individuals belonging to the most prominent families in Thebes in the eighth-sixth centuries. The title “Singer in the Interior of the Temple of Amen”, used to the exclusion of all other titles, appears to be a reflection of their social capital, and indicated their privileged access to the Amen clergy. In contrast to other groups of women, who generally included up to four titles on burial goods (such as, Lady of the House to indicate marital status; Noblewoman, to indicate social status; and professional titles such Chantress), the Singers in the Interior of the Temple of Amen used the title of Singer exclusively, although many were married and of noble lineage. There also seems to have been a conscious distancing of their identity from male associations, as the Singers were buried in independent tombs, did not indicate their spouses in and on their funerary monuments, and some emphasized their matrilineal rather than patrilineal heritage.

At Medinet Habu, today known best as the site of the Great Temple of Ramesess III (ca. 1184-1153 BCE), there is a concentration of burials of elite women. During the 8th-6th centuries, the God’s Wives of Amen, women who were royal representatives for the king in the south, constructed their tombs within the temple precinct. As the support staff for the God’s Wives of Amen, the high-ranking Singers in the Interior of the Temple of Amen, too, were interred there, resulting in a cemetery of Singers. The tombs of these women are distinctive in that they are individual tombs, which although small, were exceptional for Egyptian culture and the time period, during which any tomb would have been exceptional. The choice of burial locations exhibits both a narrative about their group affiliation and individual expressions of identities.

Within this landscape of Singers, however, one can discern attention paid to distinguishing individual identity. Although it is usually suggested that the spatial distribution of the tombs demonstrated the loyalty of the Singers to their superiors, the God’s Wives of Amen, I also suggest that the burials of the Singers, in individual tomb chambers, arrayed in the around the sacred precinct demonstrated individual identity expression through a reinterpretation of the physical markers and memories embodied in the various structures. Those interred in and near the tombs of the Gods Wives of Amen were clearly demonstrating loyalty. Others were concerned with demonstrating individual status within the group. The most distinct example is that of tomb 21, located within the interior of the Great Temple.

Tomb 21, the tomb of Nesterwy, is located at the very back of the Great Temple. Although the tradition of burials in temple precincts appeared during the early first millennium, burials within temples themselves were rare. Moreover, the situation of the tomb within the innermost, hence the most sacred, areas of the temple speaks of specialized privilege and access. Nesterwy was a king’s daughter whose birth and professional ranks entitled her to be buried in the temple, in arguably its most secure and sacred space. The wall reliefs of offerings scenes and equipment provided symbolic sustenance, allowing for the interpretation of the entire temple as a funerary chapel for her. Nesterwy, in that sense, effectively possessed a monumental tomb of the first order. Moreover, by placing her tomb in the interior of the temple she is materially constructing and displaying for eternity, her rank and title of “Singer in the Interior of the Temple.”

The physical interments and setting of the interments of the Singers at Medinet Habu seem to satisfy and express a variety of important axes of their identities. Certainly gender formed a basic structuring axis, but what seems to be of more importance was social status, both intra- and inter-group. In the rapid social fluctuation of 8th-6th century BCE society we can see most clearly the invention of traditions for the purpose of group definition. The archaeology of the burial practices of the Singers demonstrates that women seized the opportunity to redefine gender ideology and roles. In their emphasis on social and professional status, the Singers reconceptualized the identities and roles of women as more than mother, wife and daughter.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.