By Jennie Ebeling and Hilda Torres

University of Evansville

“It is important, when planning an expedition, to decide what you are going to wear. For the pop culture archaeologist the choice is simple …” (Russell 48).

From Biblical Archaeology Review March/April.

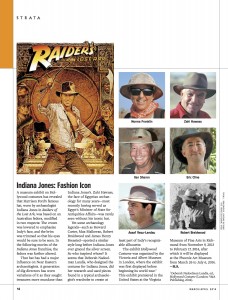

British archaeologist Miles Russell is referring, of course, to the “archaeologist as adventurer” wardrobe that originated in early 20th century cinema (based largely on the dress adopted by archaeologists of that time) and continues to define the way in which archaeologists are portrayed in pop culture. Some archaeologists perpetuate this stereotype of by dressing in the manner of famous archaeologists from the big screen. A recent article in Biblical Archaeology Review’s Strata section entitled “Indiana Jones: Fashion Icon” featured six archaeologists – four of whom currently direct excavations in Israel – wearing distinctive hats in the field presumably under the influence of Dr. Jones. Such visual clichés – which include fedoras and pith helmets as well as khaki shorts and leather jackets – have been critiqued for their “highly problematic colonial and imperial undertones” (Holtorf, 65). However, it’s hard to argue with archaeologists who find “looking the part” helpful when recruiting students, engaging the public and raising money for field projects.

Writing in 1949, American archaeologist Alfred Kidder saw little place for women when he famously identified two sorts of archaeologists: “the hairy-chested and the hairy-chinned” (1949, xi). Coupled with the military analogies frequently employed by archaeologists, who mount campaigns, endure tough conditions in the trenches, etc., it is easy to see why the public still considers archaeology to be a male enterprise. Acknowledging that field archaeology is gendered masculine, German archaeologist Cornelius Holtorf speculates that female archaeologists “may occasionally still feel pressure (or a desire) to act more masculine on excavations” (Holtorf, 42). Even Lara Croft, the most recognized female archaeologist in pop culture and thus the most recognized female “archaeologist” on the planet, “can be seen as a male protagonist in female masquerade …” (Holtorf, 71). Although a critique of Croft’s look is beyond the purview of this blog post (if you haven’t lost all hope just yet, google “sexy archaeologist costume”), we all can agree that her clothing is pretty impractical for an archaeological excavation. So how do real-life female archaeologists dress in the field and why does it matter?

Jezreel Expedition team member Nate Biondi sports a rare double-trowel-in-single-trowel holster look.

Those who have spent any amount of time on archaeological excavations in the last few decades know that the typical dig wardrobe for both women and men consists of old t-shirts and shorts or long pants, depending on the locale and climate. One might also see tank tops (see, for example, the latest “dig issue” of BAR) and the occasional bikini top in less conservative places, but concern about skin cancer has women and men more concerned about protecting skin than showing it. Hat styles vary, with both women and men usually choosing ball caps or wide-brimmed outdoorsy hats, and everyone these days is required to wear boots or otherwise heavy shoes. It’s often difficult to distinguish senior staff members of both sexes, including dig directors, from other team members since everyone is in more-or-less the same kind of outfit. Dig culture certainly doesn’t leave much room for those with some sense of personal style.

There is one item that seems to be worn more often by men than women in the field, however: the trowel holster. These now-ubiquitous accessories, which appear to have replaced the gun holsters worn by pop culture archaeologists of the past, are favored by male archaeologists who have a soft spot for khaki safari wear and similar archaeologist-as-adventurer clothing choices. This presents a dilemma for the female archaeologist: the trowel is an essential dig tool that’s good to have close at hand, but trowel holsters are masculine-looking as well as uncomfortable, since they must be worn on a belt. What to do?

One member of the Jezreel Expedition, Hilda Torres, came up with a solution: a trowel belt for women. Here is her story.

“I decided to make trowel belts because there are no feminine clothes or accessories for archaeologists; dig clothing and tool belts are plain in color and look masculine. During my first season on an excavation in Israel, I noticed that the female archaeologists would rather carry their trowels in their bags than wear an uncomfortable trowel holster on a belt, so I designed a trowel belt for women in the shape of an upside-down triangle so the trowel can be worn away from the waist and hips. After testing a prototype at home, I sewed several belts for the female members of the senior staff at Jezreel to test in the field during theseason. Since then I have made some adjustments to the pockets and the trowel holder itself, and the current design is much more spacious and sturdy. I make the trowel belts in bright and pastel colors and embellish them with Swarovski crystals and embroidered initials. They are made of lightweight material and can be adjusted to any waist size. I am still creating the trowel belts while also designing my own clothing line for female archaeologists; I have already registered the name for the clothing line and hope to have a full collection together by the end of July. When the collection is ready, I plan to have a fashion show in which I display the designs. Although still practical, the trowel belts and other dig clothing that I am designing will allow women to express their sense of fashion while working in the field.”

This step toward claiming dig fashion may seem superficial and unnecessary to some, but for young women – who comprise the majority of diggers working in Israel and many other places – it offers an opportunity to change male-oriented dig culture ever so slightly. Might a small change like this encourage archaeologists to make substantive changes that will benefit women working in the field in the future?

References

Holtorf, Cornelius. Archaeology is a Brand! The Meaning of Archaeology in Contemporary Popular Culture. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Holtorf, Cornelius. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas: Archaeology as Popular Culture. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Kidder, Alfred. “Introduction.” Prehistoric Southwesterners from Basket-Maker to Pueblo. Ed. Charles A. Amsden. Los Angeles: Southwest Museum. xi-xiv.

Russell, Miles. “”No more heroes any more”: the dangerous world of the pop culture archaeologist.” Digging Holes in Popular Culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction. Ed. Miles Russell. Oxford: Oxbow. 38-54.

“Strata: Indiana Jones: Fashion Icon.” Biblical Archaeology Review, Mar/Apr, 14.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.