By: Avraham Faust and Hayah Katz

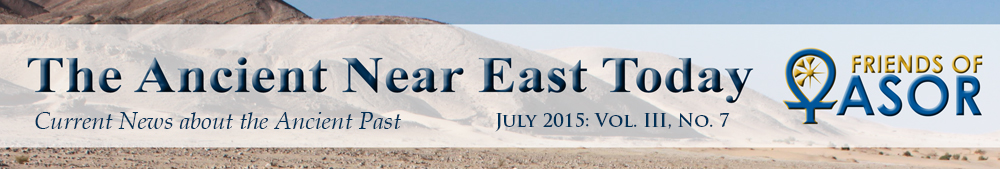

Tel ‘Eton, usually identified with biblical Eglon, is a 6.6 hectare mound located in Israel’s lowland (the Shephelah), at the edge of the trough valley which separates the lowlands from the Judean highlands. The ancient city is situated near an important junction on the north–south road and the east–west road that connected the coastal plain with Hebron.

- Aerial photograph of Tel ‘Eton. Photograph by Sky View/Griffin Aerial Imaging.

- Map of Tel ‘Eton and the roads in its vicinity (prepared by Yair Sapir), on the background geological map. Courtesy of Israel’s Institute of Geology.

Research at Tel ‘Eton

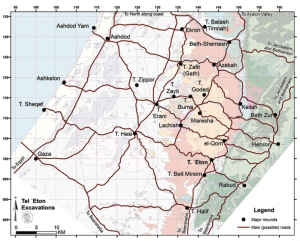

Salvage excavations in the large necropolis surrounding Tel ‘Eton were carried out in 1968 and small-scale salvage excavations were conducted in 1976 by the Lachish Archaeological Expedition. In, the Institute of Archaeology at the Martin (Szusz) Department of Bar-Ilan University initiated a large-scale excavation project at the mound and survey of its surroundings. Tel ‘Eton was chosen due to its location at the eastern edge of the Shephelah, just below the Judean highlands. While dozens of excavations take place in the lowlands, the highlands are far less known. Tel ‘Eton is located farther east than any other mound currently excavated in the region, and thus provides better information on the heartland of Judah.

Tel ‘Eton in the Early and Middle Bronze Age

Bedrock has not been reached yet, and the earliest period we uncovered so is the Early Bronze Age (EBA, ca. 3500-2000 BCE) – the first period of urbanization. Due to the depth of the remains, we reached this period only in a very limited area. The remains include a few walls, and some vessels and sherds. The repertoire appears to date to EBAIII. Although the exposure is limited, when combined with results of the survey, in which this period is well-represented, it is reasonable to assume that EBA settlement was quite significant.

No Intermediate Bronze Age (IBA) remains have yet been unearthed in our excavations, and not a single IBA sherd was found in the survey. It appears that the site, like many others in the region, was abandoned during this time. The situation in the Middle Bronze Age (MBA) is less clear. A few sherds were found in the survey, but no remains have yet been uncovered in the excavations.

A Canaanite Town: Tel ‘Eton in the Late Bronze Age

A significant settlement existed on the mound during the Late Bronze Age (LBA). Remains from this period were unearthed wherever we cut through the Iron Age II destruction layer, as well as in the few places where the 8th century remains were not found as a result of later activities. In Area B, Late Bronze remains were unearthed in practically every square and in situ vessels were even discovered down the slopes. In the only place where we cut through the LBA remains, they were about 3 m thick. All this indicates that the LBA settlement was large and dense, probably covering the entire mound.

The LBA is relatively well-known historically from Egyptian sources, especially the el-Amarna letters, which provide a wealth of information on Canaan. Based on this and results from excavations of many sites in the area it is commonly assumed that Tel ‘Eton was located between two large city-states that dominated the region, and which were Egyptian vassals. One is Lachish, located 11 km northwest of Tel ‘Eton, and the other is Hebron (or Debir) in the highlands to the east. Although Tel ‘Eton is usually regarded as a satellite of one of those, it is also possible that it was independent during at least part of the LBA.

Whatever the political status of Tel ‘Eton, the finds clearly show that it was part of the Shephelah’s settlement system and not that of the Hebron Highlands. Various finds, including petrographic analysis of the local pottery, indicate the town did not have many interregional connections, and that it interacted mainly with immediate neighbors in the southern Shephelah, like nearby Tel Halif and Lachish. Tel ‘Eton was part of a flourishing and dense settlement system.

Evidence regarding the end of the LBA town hints it was destroyed, but we must wait for more data before definite conclusions can be reached. This destruction, probably in the first half of the 12th century BCE, is part of a wider wave which affected the entire area, and whose consequences will be addressed below. It is not clear who the agents of destruction were; suggestions include the Israelites, Philistines, and Egyptians.

Negotiating Identity: Tel ‘Eton in the Iron Age I

Remains from the Iron Age I were unearthed above the LBA layer. The ceramic assemblage exhibits clear continuities with LBA forms, but includes a few bichrome Philistine sherds, which suggests connection with the coastal plain. This is further supported by finds in the so-called “Philistine tomb” unearthed west of the mound, a well-hewn rock-cut tomb with many luxury objects including metal objects, seals, and more. A few nicely preserved Philistine bichrome vessels in the tomb gave it its “name.” Theses indicate how local Canaanite elites appropriated this pottery in their negotiations with both Philistines and other groups in the area, as well as with members of the lower classes at the site itself. Iron Age I remains, however, were unearthed only in a limited part of the mound, and suggest the settlement was more limited in size than during the LBA.

The Iron Age I was a formative period, with the Philistines settling in the southern coastal plain to the west, and the Israelites on the highlands to the east. The Shephelah, located between those regions, was only sparsely settled.

Settlement at Tel ‘Eton, however, continued and the site was part of a small group that existed in the Iron Age I trough valley. Interestingly, petrographic analysis suggests that Tel ‘Eton had only limited interaction even with nearby sites like Tell Beit Mirsim and Tel Halif. Many vessels – more than during other periods – were produced at the site itself. Various evidence suggest these sites were part of a small Canaanite enclave that survived the turmoil during the transition to the Iron Age I. Local inhabitants defined themselves in contrast to the Philistines of the coastal plain and the Israelites of the highlands, and maintained clear boundaries with both via their ceramic and food culture – the rarity of pork, for example, differentiated them from Philistines, whereas the ceramic assemblage created a clear separation with Israelites to the east.

Tel ‘Eton in the Iron Age II and the Emerging Highland Monarchy

The settlement expanded significantly during the Iron Age IIA, and was even fortified. Similar changes were also observed in other sites in the Canaanite enclave, Tell Beit Mirsim and Tel Beth-Shemesh, and it appears that all were incorporated into the kingdom of Israel/Judah at this time. This is supported by the establishment of many new settlements in the Shephelah – all with clear connections with the highlands and apparently established by Israelites. It appears that Tel ‘Eton was gradually “swallowed” by the kingdom of Israel/Judah.

The Iron Age IIA settlement encompassed most of the 10th-9th centuries BCE. On the basis of evidence from various sites, it is likely that the process started in the 10th century BCE (the time of the biblical United Monarchy), although some scholars advocate a later date within the Iron Age IIA. The inhabitants of Tel ‘Eton gradually assimilated with the Israelite/Judahite majority and eventually became Judahites.

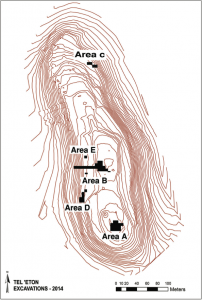

- The plan of the governor’s residency in Area A. Prepared by Yair Sapir and Segev Ramon.

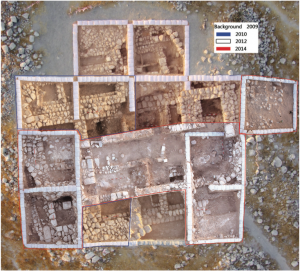

- Aerial composite photograph of the governor’s residency in Area A. Photographs by Sky View/Griffin Aerial Imaging; prepared by Segev Ramon and Tamar Olenick.

Tel ‘Eton in the 8th Century BCE: A Judahite Center

Most finds from our excavations and survey are from the Iron Age IIB (8th century BCE), and remains dating to this period were uncovered in practically every excavation area and square.

Among the finds are a number of dwellings in Area A, including Structure 101, which we call the governor’s residency. This is a large long house built following the four- room plan, and whose ground floor covers some 230–240 m2. Its location at the highest point on the mound, with a good view of the mound and below, size and high quality of construction, as well as the finds, led us to interpret it as a governor’s residency.

The structure was almost completely excavated, including a large yard and a system of rooms to its north, west, and south. Hundreds of artifacts were unearthed, including a wide range of pottery vessels, loom weights, metal objects, botanical remains (many still in the vessels), as well as many arrowheads, evidence of the battle that accompanied the occupation of the site by the Assyrians. A small collection of bullae and sealings found in the building indicate its the significance.

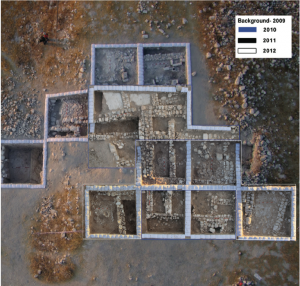

Part of another residential neighborhood was discovered in the upper part of Area B, where parts of at least five structures were unearthed along with many in situ finds. Segments of additional buildings were also exposed in the lower part of Area B. Parts of three buildings, built parallel to the city wall, were uncovered in Area D and remains of a few walls, damaged by later activities and pits, along with a clay installation, were uncovered in Area C.

- A composite aerial photograph showing the Iron Age IIB architectural remains in Area B (upper part).

- A composite photograph of the fortifications and other remains in Area C. Photographs by Sky View/Griffin Aerial Imaging; prepared by Segev Ramon and Tamar Olenick. All rights reserved by the Tel ‘Eton Archaeological Expedition.

Fortifications, some securely and some tentatively dated to the Iron Age, were discovered in three areas. In Area D, a massive 4 m wide wall was unearthed. In Area C, an even broader wall was exposed. The wall uncovered in Area B was also massive but we have not yet removed the later accumulation on its inner side, and so cannot exactly determine its width. The distribution of finds, and even the location of the city walls, suggest that settlement was quite large, and covered almost the entire mound.

The importance of Tel ‘Eton is also demonstrated by the small collection of bullae and sealings within the large building (governor’s residency) in Area A. Although bullae are common in the 7th century BCE, they are surprisingly rare in 8th century BCE destruction levels. The small collection therefore indicates the site was a relatively important center. This small collection from Tel ‘Eton is also important for our understanding of the development of administration in Judah.

The large size of the site, the relatively high percentage of non-local pottery, additional finds such as the only 8th century BCE collection of bullae and sealings discovered in Judah, and the unique governor’s residency, indicate the site had a central role within the Judahite settlement system and administration. We have suggested that the highlands were the center of administration, and the Shephelah was the periphery, and that as a result of Tel ‘Eton’s location in the trough valley it was more central than most sites in the Shephelah, and had a prominent role within the administrative structure of Judah.

701 BCE: Sennacherib’s Destruction

This large and prosperous settlement came to an end in a violent destruction, probably inflicted by the Assyrian army during the campaign of Sennacherib in 701 BCE. All sources indicate that Judah suffered a major blow but that the kingdom was not destroyed, and that the capital, Jerusalem, was spared. The Shephelah, however, was thoroughly destroyed and was torn from Judah. The finds from Tel ‘Eton exemplify this reality; a heavy destruction layer was uncovered in practically every area and every square.

- The Assyrian destruction layer: room 101D (Area A). Photographs by Avraham Faust.

- The Assyrian destruction layer; room 101E (Area A).

- Part of the ceramic assemblage from the Assyrian destruction layer (after the fifth season). Photograph by Avraham Faust. All rights reserved by the Tel ‘Eton Archaeological Expedition.

Like most sites in the Shephelah, after the massive Assyrian destruction of the city in the late 8th century BCE, it was not rebuilt. We have limited evidence of reoccupation on the ruins in some parts of the city but this represents only a short episode that occurred immediately after the destruction. Clearly, Tel ‘Eton suffered greatly as a result of Sennacherib’s campaign. The gap in the occupation of the site continued through the 6th and probably also the 5th century BCE.

Later Occupation

Settlement, on a much smaller scale, resumed in the 4th century BCE, the late Persian period. Although much more limited than the Iron Age II, it was still covered large parts of the site. The architectural finds include a large fort in Area A, reuse of buildings in Area B, pits and more.

On the basis of the pottery, a few carbon 14 dates, as well as a few ostraca (dated on the basis of paleography), we tentatively date this settlement to the 4th century BCE into the 3rd century BCE. The southern trough valley was then part of Idumaea, and although we know very little of this political unit, it appears that Tel ‘Eton was a central site in this region, with a fort surrounded by a village. The petrography indicates strong contacts with the highlands, and the percentage of pottery that originated there (48%) is much higher than in any other period.

A composite photograph of the Persian-Hellenistic fort (Area A). Photographs by Sky View; prepared by Yair Sapir and Michal Marmelshtein. All rights reserved by the Tel ‘Eton Archaeological Expedition.

We cannot rule out a farmstead or another isolated building on the mound but it appears that there was no real settlement after the 3rd century BCE. It seems that during the Byzantine period much of the site was used for agriculture, and that much of the current form of the mound is a result of agricultural terracing activity conducted at the time. The people who built the terraces changed the shape of the site, moving earth around to create their desired pattern. Additionally, soil was taken from the mound to fertilize the fields in the area.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

Pingback: Excavating Over 2,000 Years of History at Tel ‘Eton | ASOR BLOG | Talmidimblogging

Pingback: Shared from ASOR | Talmidimblogging