By: Jan P. Stronk

Though I was acquainted with the figure and work of Diodorus of Sicily, it only became familiar to me thanks to my work on another Greek author, Ctesias of Cnidus. Fifteen-odd years ago, I started to work on the Persica (Persian History) of Ctesias, an early fourth century BCE physician and author, who allegedly had spent seventeen years at the Persian court. Having returned to the Greek world, Ctesias wrote, amongst others, a history of Persia based, as he claims, on sources he found in the Persian so-called royal libraries. My work resulted, so far, in papers in several journals and a conference-proceedings (Josef Wiesehöfer/Robert Rollinger/Giovanni B. Lanfranchi (eds), Ktesias’ Welt/Ctesias’ World (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz)), as well as in the first part of Ctesias’ Persian History (Düsseldorf: Wellem-Verlag), presenting an introduction, the text, and a translation.As most direct evidence of Ctesias’ work was lost in the mist of time, we have to rely on the evidence provided by other sources to create the best image possible of his work. Such evidence was produced by many ancient authors, some quoting only some words, others a few lines, others again even some paragraphs, by the ninth century CE Byzantine Patriarch Photius (who devoted a relatively long part of hís Bibliotheca to the work of Ctesias), and especially by Diodorus of Sicily, who refers relatively extensively to (and quotes from) Ctesias’ work in the only work we know of Diodorus, the Bibliotheca Historica. Within the framework of my work on Ctesias (currently preparing a historical commentary to it) it made, therefore, sense to devote special attention to the Sicilian author and notably what he had his audience to tell about the ancient Near East, not merely based upon Ctesias’ work but also on that of many others.

Diodorus of Sicily, a Greek, was born as a member of an obviously well-to-do family in Agyrium on Sicily c. 90 BCE. He spent some years in Egypt (from about 60 BCE) and then travelled to Rome, where he more or less settled and started to write his Bibliotheca Historica (Historical Library), a work in forty books (= chapters), which took him some thirty years. Regrettably, part of this work was lost: only books one to five and eleven to twenty survive (nearly) completely, the rest does so in a fragmentary state. The last complete copy of the work is said to have been destroyed in 1453 CE, when the Ottoman army took Constantinople, but before that time, parts of Diodorus’ work already had found their way into many other ancient and Byzantine sources.

So much for the backgrounds of the work. But what makes this work so valuable, not merely for me but for many ancient historians? The answer is hidden in the work’s title: in the end, it effectively is a library. To compose his work, Diodorus based himself upon the work of previous writers, some mentioned by name, more by indication (altogether at least some 144 authors can be traced). Following this method, Diodorus preserved fragments of many works now partially or even completely lost while he described the history of the East, of Greece, Sicily, Carthage, Rome, the vicissitudes of Alexander the Great and the Diadochs’ Empires. Equally important is that Diodorus’ work is our sole written witness for certain periods and/or occurrences, a reason why we should not underestimate the meaning of the Bibliotheca.

Nevertheless, underestimation has prevailed in later judgements on Diodorus. Notably, classicists have judged exceptionally cruelly on the Bibliotheca, especially in the later nineteenth and early twentieth century. Such judgements left their traces, continuing well into the latter part of the twentieth century. Part of this may be understandable if we only look at the manner Diodorus treated his sources and forget the tremendous amount of material he does provide us with, material we would not have but for him, nuances –sometimes important ones- we now can apply, but which would have been impossible without the Historical Library. Therefore, while conceding in full his obvious flaws, some of them caused by his biases, our final judgement on him should be much more positive than it, largely, still is today.

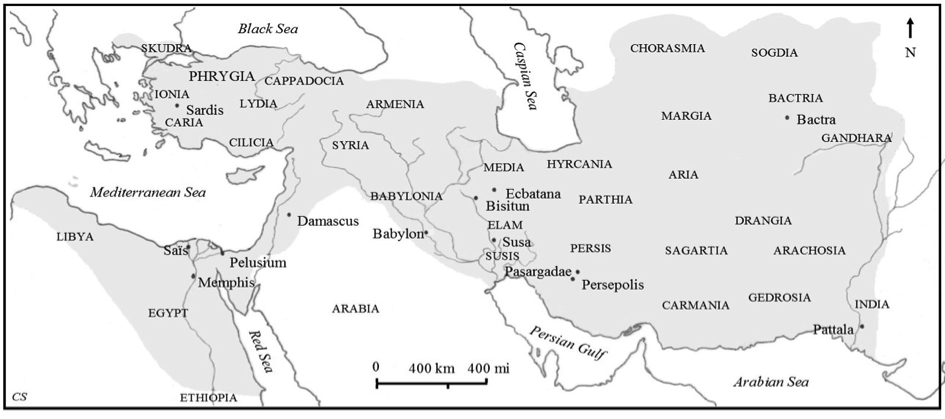

The extent of the Achaemenid Persian Empire; drawing from Semiramis’ Legacy, p. 156, © Clio Stronk

Because the ancient Near East, especially the history of ‘Persia’ (a much wider concept than modern Iran), was and still is a major focal point of my research, I decided to dedicate a separate book to Diodorus’ treatment of Persian history, viz. of the realms of which the ancient region of Fārs (roughly to be equated with Persis) formed part. As the information Diodorus provides on the subject is rather scattered throughout his work and/or hard to assemble and access, I believed –and still do so- such a book could fill a lacuna. Diodorus starts his ‘Persian’ account with the Assyrian Empire, notably with Ninus –the eponymous founder of Nineveh- and his wife and successor Semiramis, then discusses the allegedly last Assyrian ruler Sardanappalus, and continues with the Medes, the Chaldeans, the Achaemenids, Alexander the Great, the latter’s Successors (= Diadochs) and their empires, ending with the collapse of the Seleucid Empire, the ascent of the Parthians, and the entrance of the Romans into the Ancient Near East. My Semiramis’ Legacy: The History of Persia According to Diodorus of Sicily (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, published in the series Edinburgh Studies in Ancient Persia, series editor Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones) comprises the whole of this story.

F. Lloyds (c. 1853), design for the scenery for ‘Sardanapalus’, an 1821 historical tragedy by Lord Byron, amongst others based upon Diodorus (c. 1853 performed in the Princess’s Theatre, London –producer Charles Kean), watercolour and bodycolour, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

I first selected those parts of the Bibliotheca that qualified for this translation. Next, I translated these parts, using all information provided by the (medieval) manuscripts on which the modern editions of the Bibliotheca are based, which occasionally but necessarily led to a different reading of the text (as an ancient historian I often look at texts from a slightly different angle than pure classicists). I believe a new translation was needed because the Loeb edition (the twelve bilingual volumes of the Loeb Classical Library edition of Diodorus’ work, so far the most accessible complete edition of the Bibliotheca, certainly for an English speaking audience) is already becoming a bit obsolete and only offers very little historical background information. My book aims to provide much more of such information in the footnotes accompanying the translation (though also textual information, especially where and why I deviated from the standard editions). By writing this translation, I could (in the introduction and concluding chapters) also pay attention to some of Diodorus’ pet-subjects: the idea of continuity of empire (hence the title Semiramis’ Legacy), the alleged Oriental taste for luxury, depravity, and effeminacy (being predominantly a Greek propaganda instrument), the need for and rewards of aretē or ‘virtue’ (a much wider concept for the Greeks and Romans than for us), and his biases (Stoicism above all, a tendency to Greek –notably Athens-inspired- chauvinism, to name some conspicuous ones). That some of these pet-subjects coloured Diodorus’ rendering of the information he provides us with is obvious, but generally it can be recognised when he does so. Therefore the final verdict on this work should be, in my view, that certainly for our understanding of the history of the ancient Near East we are, as yet, in the end, lucky to have Diodorus’ Library. Ultimately though, it is such an exceptional –and often charming- work that I found (and still find) it a pleasure to read it time and again for its own merits and not only because it forms a solid base for a historical commentary on Ctesias’ Persian History.

Jan Stronk is Research Associate in the Department of Ancient History at the University of Amsterdam. The author of Semiramis’ Legacy: The History of Persia According to Diodorus of Sicily.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

Pingback: Friday Varia and Quick Hits | The Archaeology of the Mediterranean World