Archaeological excavation photography (AEP) is a means of documentation vital to both the historical and archaeological record. I began AEP several years ago after being frustrated over the availability of good quality photos for my doctoral dissertation. It was an off-handed remark by a colleague about my excavator's eye for detail that had me wondering what constituted great AEP. For many, photography in the field consists of scrambling quickly to document discoveries, often using a point-and-shoot mentality with little or no thought -if the budget allowed- that a professional photographer might be available to take better publication- quality pictures, which would likely involve considerably more time. I would further submit that the traditionally-trained archaeologist, who has also mastered the art of quality photography, sees an artifact, a balk, or stratigraphy in a different light, noting subtle details a standard photographer might overlook.

In many respects, the advancement of technology has left traditional photography behind. Photogrammetry, 3D imaging, computer reconstruction, editable digital photography, and ground-penetrating radar, have allowed us to simulate full reconstructions of a site. However, as many of us on excavations know, some projects may not have the funding for this equipment, nor might they have the means to move these devices across borders in the Middle East. Further the use of many of the techniques mentioned above is not an accepted alternative for publication purposes. And despite smartphones and computers being at our fingertips these technological advances have been an inadequate replacement for good archaeological photography. I propose that the best record of an archaeological site results from the blending of high quality digital photography with classical field archaeology. This type of AEP can potentially serve as a baseline for more advanced photogrammetry and site documentation. It is important to note that I am not an advocate of AEP only, but rather its use as a baseline for site documentation.

Image courtesy of Brandy Forrest with permission from the Tall el Hammam Excavation Project

This is a primary example of the difference between a professional photographer and a trained archaeological photographer. In being assigned to photograph a plaster floor, a professional photographer might capture just the floor, however as an archaeological photographer, it is not only the importance of the plaster floor but how it intersects with the plaster wall. These are clearly demonstrated in this image.

Image courtesy of Brandy Forrest

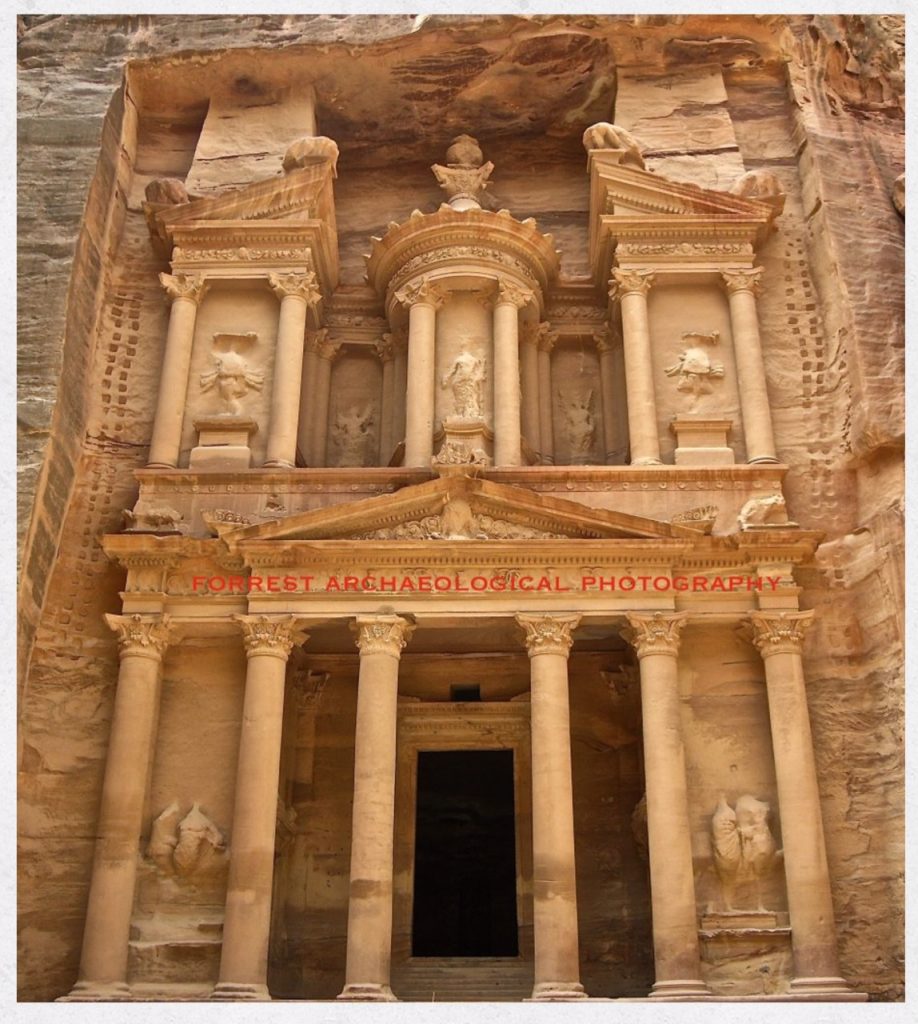

One of the most frequently photographed sites at Petra, the treasury is not just about the building itself, but also the workers who built it. The eye of an archaeologist and photographer notes the placement of the small footholds used by the workers overyears ago to build the ancient city of Petra, which are clearly evident in this image.

The next question one might ask is how does AEP differ from professional photography. The answer is simple: time and detail. Most professional photographers - whether in a studio or general setting - require a lengthier set up to capture an image. When artifacts are brought into a laboratory setting for analysis, the available time for a photographer to create documentary photos is increased, but the reality of being in the field is very different. For a lone photographer, it can be problematic when multiple finds are unearthed, or loci change, or architecture is revealed, to get more than a few seconds to set up the camera, let alone time enough to take the camera out of automatic position or adjust the ISO and lighting. This often leaves us with images that while useful for balk drawings, may not be publication worthy. Time can be at a premium, especially when multiple squares are calling for your services, so yes, feel free to snap an image with your cell phone. But it is the trained excavator/photographer who has the unique ability to see an artifact in situ and immediately know how and where to place the measuring apparatus, adjust for lighting, and minimize shadows - all while shooting in automatic mode- to get the cleanest photo possible in one minute or less. Some would even consider this method of photography 'old school'.

There are several keys to achieve quality AEP in addition to having the eye/talent for this type of photography. For me, two stand out.

Tip No. 1:

Ensure the square being photographed is prepared properly. Adequate cleaning is essential and significantly reduces the amount of time required to take the photograph. This includes trimming and cleaning (even marking) balks, as well as sweeping and removing loose dirt and debris.

Tip No. 2:

Focus on the sunlight, shadows and the details of the locus or object. My goal when capturing an image is to clarify detail as accurately as possible.

Image courtesy of Brandy Forrest.

As an archaeological photographer the details in an image are of the utmost importance. Capturing a Roman Mile Marker and not missing the Hebrew and Greek writing present in the image are essential skills that differentiate the general photographer from the archaeological photographer.

Image courtesy of Brandy Forrest with permission from the Tall el Hammam Excavation Project.

This example demonstrates the clarity of the Roman wall as well as the intersection of an older Middle Bronze Age structure. The image not only documents this section of excavation but also gives perspective against the backdrop of the larger geographical area.

A photographer who understands what is seen through the camera lens is more efficient, can respond quickly, typically in under a minute. Such is important for an excavation to run smoothly. The images found all reflect archaeological excavation photography and the method I have described above. In my experience, dig directors frequently appreciate having a versatile photographer who understands the intersection of archaeology and photography, as well as the ability to accomplish publication-worthy photos in minimal time. As AEP photographers, the reality is that if we fail to document a discovery correctly, we fail in our obligation to archaeology and ultimately to history. Furthermore, with the reality that treasured archaeological sites face unprecedented perils beyond our control, good photography is a critical link in preserving sites for future generations. After all, as one of my favorite dig directors likes to remind all of his volunteers, "Make sure it's photographed correctly, 'cause once it's out of the ground, you can't ever put it back."

Brandy Forrest is a Doctoral Fellow with Trinity Southwest University and a Field Archaeologist with the Tall el Hammam Excavation Project. She is also the owner and operator of Forrest Archaeological Photography.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

Pingback: Explorator 19.44 ~ February 26 | Explorator