By: Kelly J. Murphy and Justin Jeffcoat Schedtler

The funny thing about the apocalypse is that it has never happened, and yet it is always in our face and right around the corner. Consider the just released Netflix series “Santa Clarita Diet,” which one reviewer notes, “gives the zombie apocalypse a refreshing new origin story.” Or a New England bookstore’s recently updated “Current Affairs” section, now stocked with “post-apocalyptic fiction.” And the infamous Doomsday Clock, which inched a half-minute closer to midnight (read: The End) as Januarydrew to a close.

The idea that the apocalypse is both always-and-never-here led us to write Apocalypses in Context: Apocalyptic Currents Through History (Fortress Press). As scholars who both teach and write on ancient apocalyptic texts and their manifestations throughout history, we wanted to explore a series of questions: What, if anything, connects ancient texts such as Daniel or Revelation to current political crises? To ecological concerns? To popular television shows, movies, and video games? How does the apocalypse stay the same, and how does it change? Our goal was to illustrate that apocalypses come in all shapes and sizes, including both the contemporary understanding of apocalypse as the end-of-the-world and the ancient notion of apocalypse as an unveiling of the world around us. Apocalypses are everywhere, from our art, climate debates, philosophies, politics, and beyond.

Chalkboard outside “The Bookloft” bookstore in Great Barrington, MA.

Cover of Apocalypses in Context

At the same time, we also wanted to demonstrate that apocalyptic convictions are often explicitly grounded in biblical worldviews. As the volume grew, we discovered that we didn’t have to look far (or even particularly hard) to find examples. In recent months, it has been particularly easy in the realm of politics. For instance, consider Dick Morris and Eileen McGann’s book Armageddon: How Trump Can Beat Hillary, which clearly draws on the (in)famous biblical language of Armageddon. According to the back cover, “Theelection is truly America's Armageddon—the ultimate and decisive battle to save America, a fight to defeat Hillary Clinton and the forces seeking to flout our constitutional government and replace it with an all-powerful president...” Or how, in response to the BREXIT vote, Franklin Graham (son of evangelist Billy Graham) alerted his Facebook followers: “We don’t know what the #EUReferendum vote means long-term, but I know that this is at least a temporary setback for the politicians in this country and around the world who want a one-world government and a one-world currency. The Bible speaks that one day this will take place.” Both of these comments underscore how, though it is not always clear to the uninitiated, ideas about the apocalypse are very often built on specific interpretations of ancient biblical stories, especially those which look toward some kind of cataclysmic End of Days. So while the term “Armageddon” is often tossed about in popular culture, from the 1998 Bruce Willis and Ben Affleck film of the same name to video games like Mortal Kombat: Armageddon, the word can be traced back to the New Testament book of Revelation, the site of a final cosmic, dualistic battle between Good and Evil (16:16).

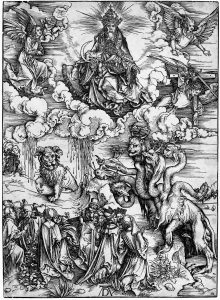

The Revelation of St John by Albrecht Durer.

Likewise, the idea of a one-world government arises out of later interpretations of various biblical passages. For example, Revelation describes a beast whose power stems from Satan (13:3-4), who will have authority over a vast empire, over “every tribe, people, language, and nation” (13:7), and will be worshipped by all the “inhabitants of the earth” (13:8). Likewise, the book of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament famously depicts a series of beasts who rise out of the sea, including a fourth beast “terrifying and dreadful and exceedingly strong,” (7:7-8) who shall “devour the whole earth, and trample it down, and break it to pieces” (7:23). Imagery such as this provides inventive minds rich resources with which to imagine that the grotesque imagery and fantastical characters represent persons and entities from their own times and places. Such readings fuel much apocalyptic speculation.

We found, as others have, that the ways in which often-obscure biblical imagery is used to create fear-inducing panic is often downright scary. After all, an apocalyptic imagination can be used as a weapon against whomever the interpreter chooses. One’s own circumstances can easily be projected onto a mythical battlefield where allies are simply identified with the cosmic Good and enemies are aligned with the Bad. The ascension of Steven Bannon to the ranks of special advisor to the President has very recently illuminated this tendency. In a recent Huffington Post article, Paul Blumenthal reveals that Bannon believes the United States sits at a pivotal turning point, a so-called “Fourth Turning” which, like past events in U.S. history (American Revolution, Civil War, WWII), results from a major crisis. When Bannon talks about a “new political order” that will arise from this “Turning” and a leader (“Champion”) who will shepherd the nation during this tumult, he is—consciously or not—appropriating apocalyptic language and ideology. It is both always-and-never-the end.

Of course, a tour of the long history of the apocalypse also reinforces how often apocalyptic thought is also a catalyst for hope. After all, one consistent, if often overlooked, theme in the biblical apocalypses is precisely the theme of hope. So while ancient apocalypses like the book of Daniel or the book of Revelation look forward to a time when the faithful will receive eschatological rewards despite their present suffering, so too do contemporary apocalypses. The theme of hope moves forward with the apocalypse, though in sometimes different ways: apocalyptic films that seek to initiate change in their viewers (e.g., Insterstellar) to video games designed to teach about climate change with the hope that we might turn the tide before it is too late for our world.

Reading the apocalyptic currents that ebb and flow throughout our literature, films, politics, art, and beyond, one thing seems certain: the apocalypse, in its many forms, has generative power, both destructive and hopeful. And the funny thing about the apocalypse is that while it has never happened, it is also always happening and right around the corner, and people at every moment get to choose which of those paths they take.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.