By Richard Elliott Friedman

By Richard Elliott Friedman

For too long Biblical studies was made up of Bible scholars who weren’t trained in archaeology or historical method. And then for too long we leaned on archaeologists who weren’t trained in biblical texts, their history, language, and authorship. Father of Biblical Archaeology William F. Albright’s ideal was that eventually the two would work together. They separated for a while, but their inevitable reunion has begun.

We can read a story closely, excavate the earth carefully, and figure out what happened that led to that story. And one of the first fruits of this high-yield merger of literary study, historical study, and archaeology is a grasp of what happened in Egypt all those years ago, the story behind the story.

I mean real textual evidence, not just reading the Bible and taking its word for it that sticks became snakes and seas split. And how does this connect with the archaeological evidence? And I mean real archaeological evidence — findings, artifacts, material culture, stuff — not just surveys that didn’t turn up anything.

The starting-point, widely recognized, is that there were Western Asiatic people in Egypt. Call them: Asiatics, Semites, Canaanites, Levantine peoples. These aliens were there, for centuries, and they were coming and going all along, just not in millions at a time.

The second step was to identify a group among these as the Levites. They are the ones in Israel with Egyptian names, the ones who foster circumcision, a known practice in Egypt, the ones with connections to Egyptian material culture: a Tabernacle that has parallels with the battle tent of Rameses II, an ark that has parallels with Egyptian barks.

It is their stories (the E, P, and D sources in the Biblical text, but not J) that have a series of known items of Egyptian lore: the hidden divine name, turning an inanimate object into a reptile, the conversion of water to blood, a spell of three days of darkness, death of the firstborn, parting of waters, death by drowning, and stories of quotas for brickmaking and the use of straw in mudbrick — also Egyptian practices.

It is only those three Levite sources that tell the story of the plagues and exodus itself, and only those three give laws about treatment of slaves. Only those Levite sources command that one must never mistreat an alien. They say the alien is to be treated the same as an Israelite, 52 times, “because you were aliens in Egypt.” But this never occurs in the non-Levite J source, or anywhere else in ancient Near Eastern law.

And genetically, the so-called “Cohen gene” isolated by analyzing Jewish genomes reflects an apparent commonality among the Aaronid priestly group that separated from the rest of the Levites; but there is no clear Levite-specific genetic signature. Cohanim, starting from a small group, perhaps a family or clan, should be related genetically. Levites, starting from a large, diverse group of immigrants from Egypt, should be diverse genetically. And that is just what the genetic research showed.

The Exodus (The Exodus Book)

Sinai Peninsula from space (Wikimedia Commons)

This evidence takes some chapters to tell in The Exodus, a work of detective non-fiction, with details, sources, and acknowledgement of the many Bible scholars and archaeologists who contributed the pieces. I’ve rattled off that evidence in a paragraph here. But even this little précis should convey that we are at last dealing with tangible, mutually supportive, data that reflect both text and archaeology.

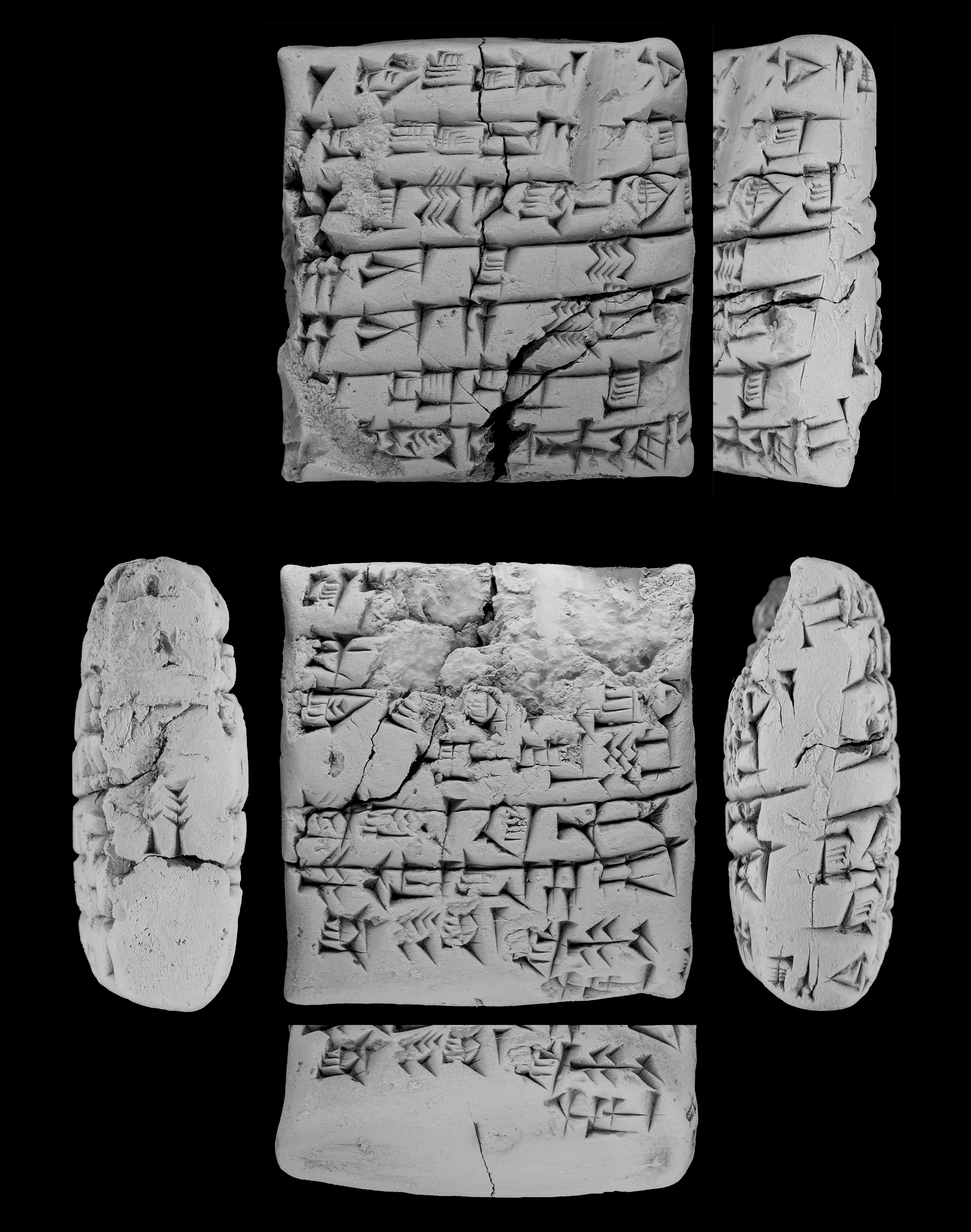

If it was just the Levites, other classic arguments, too, are transformed. One of the turning-points in many arguments about the exodus has been the Merneptah stele. Pharaoh Merneptah’s inscribed stone contains the earliest known occurrence of the name Israel. Scholars date it to circa 1205 BCE or a little earlier. So, scholars said, if Israel was a settled people by 1205, then the exodus had to be before that. But this still presumes that all of Israel made the exodus and then arrived in Canaan. If it was just the Levites who made the exodus, while the rest of Israel was back in their land, then this whole argument disappears. The Levites’ exodus could have been before or after Merneptah. As Biblical scholar Abraham Malamat said, “This stele has little or nothing to do with the Exodus.”

People who challenge the historicity of the exodus frequently point to the absence of any references to it in ancient Egyptian sources. This too is dependent on an assumption of a big exodus of a mass of Israelites. There is no reason to be surprised that there’s no mention of Israelites in Egypt when, after all, there’s no mention of Israelites in the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15 either!

A group of Levites, of unknown size, leaving at an unknown time, under unknown circumstances, didn’t require a headline in the Egyptian Daily News. People are looking for a reference to a specific nation, Israel. But no entity named Israel was there. And the group that was there would not necessarily be called “levites” in Egyptian sources either because that might not have been the name by which they were known there. levi was a Hebrew word for an attached person, so a levite group in Egypt probably was not known to Egyptians by that term. We have no idea what they’d be called there.

Some ask: why aren’t the pharaohs’ names in the Torah given? They argue that this is evidence that the stories were invented by writers who had no idea of the names of ancient pharaohs. But on the hypothesis that the oppression and exodus of the Levites are historical, we must consider whether there could be other reasons why the pharaohs are unnamed. Perhaps the names of the pharaohs were simply no longer preserved in memory or written tradition by the time the stories were written.

The authors had no sources that recorded (or cared about) the pharaohs’ names. They cared about names that mattered much more to them: Levi, Moses, Aaron, Miriam, Zipporah, even the midwives Shiphrah and Puah. These are names of the story’s heroes. But did the authors care whether it was Pharaoh Rameses II or III? Or Merneptah? Apparently not. An absence of pharaohs’ names doesn’t mean an absence of an exodus. Indeed, there may not have been any single pharaoh’s name to remember. On the hypothesis that there were Levites, “attached” outsiders, in Egypt through centuries, who then left, we don’t know if any one pharaoh stood out as their prime oppressor.

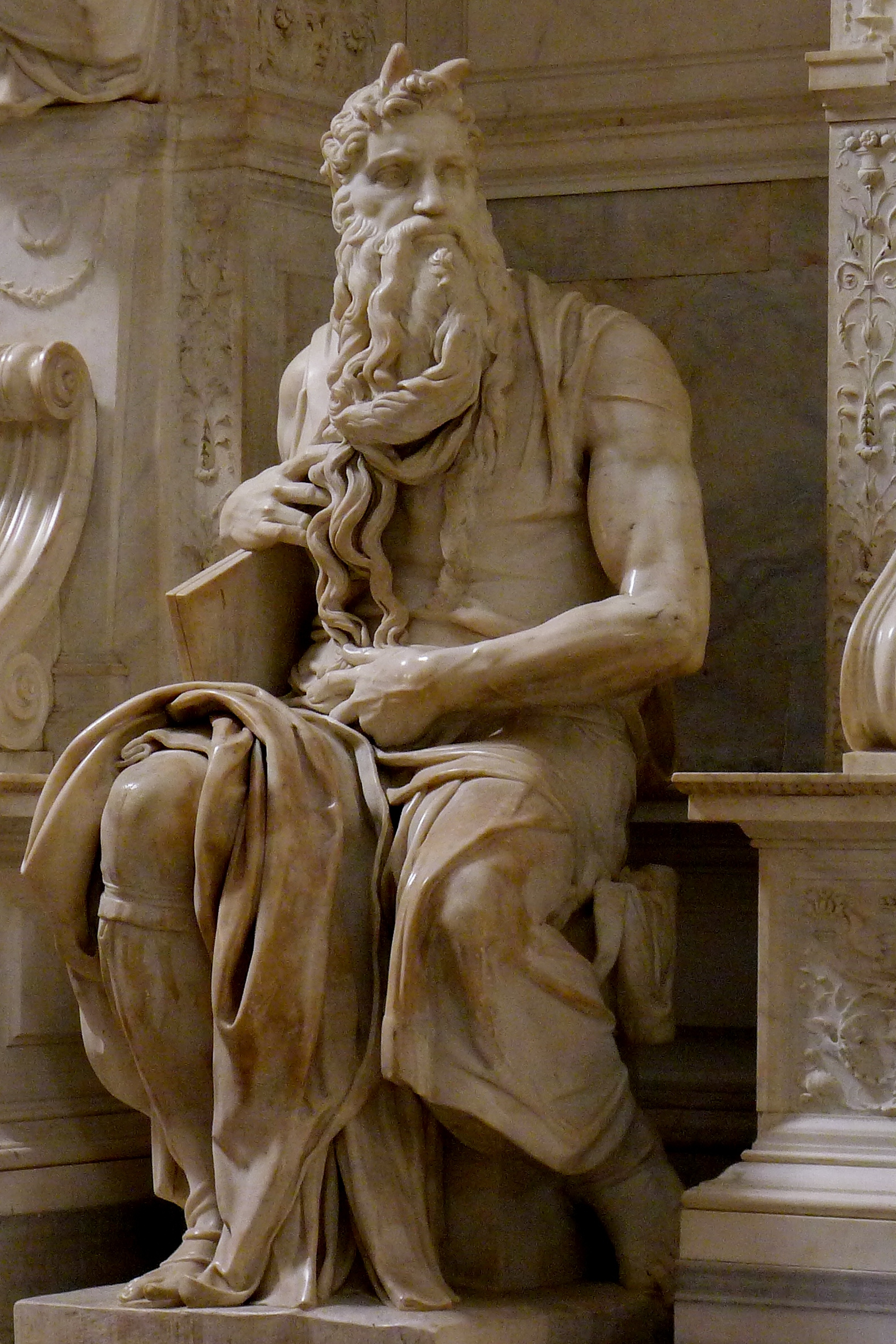

Michelangelo, Moses (Wikimedia Commons)

Merneptah stele (COJS)

The principal points that people raise in doubting the exodus are mostly about numbers: We’ve found no remnant of the two million people in the Sinai region, no widespread material culture of Egypt in early Israel, no records in Egypt of a huge mass of Israelite slaves or a huge exodus.

True. But none of this is evidence about whether the exodus happened or not. It is evidence only of whether it was big or not.

The likelihood that just the Levites were the ones who experienced the exodus forces us to reexamine many of the classic arguments. Either these arguments involve a mass exodus of all Israel, or they don’t come to terms with connecting the archaeology with the texts and their authors.

In the age of cyber-archaeology, sophisticated literary study, and advanced linguistic knowledge of biblical Hebrew, we can get at the story behind the story. And here’s the pot of gold at the end of this particular historical rainbow: we don’t have to choose between recapturing the history and caring about the values we might derive from the exodus. Once we exhume the history, we’ll find, more intensely, more vividly, more really than before, the fruits that those events bequeathed for all the centuries that followed since then.

Richard Elliott Friedman is the Ann and Jay Davis Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Georgia.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

Pingback: The Exodus in Archaeology and Text — The ASOR Blog | Talmidimblogging

Pingback: Did the exodus really happen? - the Way?