ANE Today Editorial Introduction:*

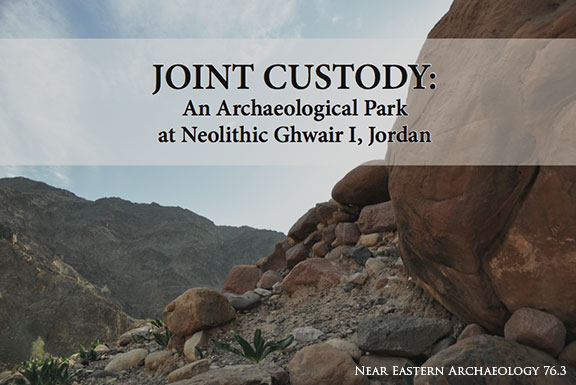

Ecotourism is quickly becoming a means for the public to appreciate archaeological sites, even in remote regions. We are pleased to present this article by Alan Simmons and Mohammad Najjar abridged from the latest edition of Near Eastern Archaeology on a case study from Jordan.

By: Alan H. Simmons and Mohammad Najjar

Edited and abridged from NEA 76.3: 178-184

The early history of archaeology in the Near East was a one-way process in which Western archaeologists took much from host countries but returned little. Now countries in the Near East have sophisticated antiquities services that are conscious of their heritage. Most welcome foreign projects, and while joint endeavors are now common, much of the intellectual output of is still one-sided. This problem is even more pronounced when it comes to public and community outreach.

A primary goal of archaeology should be educational, and site accessibility and community outreach are clear components. Part of this includes the preservation and presentation of sites from all periods. But how to select which sites to showcase, especially in regions such as the Near East where there is such a huge time range of human occupation and countries with limited budgets for heritage preservation? Sites of classical antiquity receive the bulk of preservation funding. Remains are spectacular and there is no denying the attraction, as well as the tourist dollars these generate. Such sites also often have ethnic, political, or religious significance, which may contribute to their status.

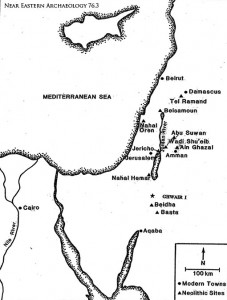

NEA Figure 2: Map of the southern Levant, showing the location of Ghwair I. Map commissioned by A. H. Simmons.

Public outreach and preservation are particularly restricted for prehistoric sites. These usually lack the visual impact of later cultures, and their significance is not obvious to non-specialists. Here we discuss a simple archaeological park at a prehistoric site we excavated, the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) village of Ghwair I in the Wadi Faynan of southern Jordan.

Prehistoric sites are rarely accorded attention, beyond a few signposts. For example, in Israel at the Tabun Caves sites from truly “deep” antiquity have been developed and even include “sound and light” presentations. In most cases, however, prehistoric sites are not considered informative enough to devote scarce resources towards public presentation. But, with the proper “packaging” these can be made interesting to the general public. For example, in the United States, many sites that lack impressive architectural features are successful at attracting visitors with minimal, but effective, “advertising.”

Archaeological sites, even spectacular ones, are highly fragile places. High public interest and susceptibility to inadvertent or deliberate damage places site managers in a difficult position: how to both preserve and protect heritage and at the same time how to make it accessible to the interested public? Are these conflicting goals?

NEA Figure 3: Prehistoric Tabun Caves in Israel, showing stratigraphic sequence. Photograph by A. H. Simmons.

One solution is the archaeological park. Low-impact parks primarily consist of well-defined trails. There are several elements for a good, trail-based interpretive program, but all begin with the physical layout of the site. What is the nature of the soil, what features are to be interpreted, are visitors allowed into the sites or just allowed to look at them, and how do the sites fit into the landscape? Also, are there physical barriers, handicap accessibility, special hazards or points of interest, and are any portions of the sites too fragile to allow visitor contact or artificial illumination?

Another important issue is the target audience. Many professional archaeologists would be happy to have sites off-limits to the public. That is both arrogant and unrealistic. Are audiences cruise ship tourists who will spend an hour and take a lot of photos? Foreign nationals who come expecting detailed explanation of the entire archaeological context? What about citizens of the country, from both urban and adjacent regions? Jordanians come because sites may be important to their heritage; others because they are interested in the area or time period.

Given the ecological sensitivity of many areas, some scenarios are not attractive. If the region is to be developed for the public, then a limited numbers of ecotourists looking for a “natural experience” is preferable to large busloads of day-tripping tourists and massive group tours. Certainly ecotourism and cultural tourism are helping drive attempts to conserve natural and cultural resources. Such approaches are already being implemented in the Wadi Faynan region, falling partially within the Dana Nature Reserve, which provides ecotourism opportunities.

NEA Figure 4: A tour bus parked outside of a Bedouin settlement at Wadi Faynan. Photograph by A. H. Simmons.

Another significant issue is cost, from the initial cost of construction to the often much higher long-term maintenance expenses. Good design can minimize but not eliminate maintenance costs.

Now we present a Neolithic case study. Ghwair I is a PPNB community located in the remote, but spectacular, Wadi Faynan system of southern Jordan). Its architecture is exceptionally well preserved and it has a broad open plaza or “public area” facing a wide series of outside steps. We undertook a major campaign of excavations at the site, and while its significance is considerable, we also are acutely aware that Ghwair I is both a fragile resource and has tremendous educational potential.

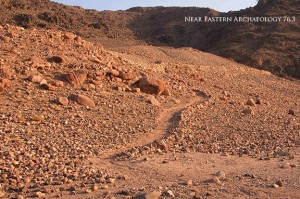

At Ghwair I, we sought to contribute to the educational experience and community outreach in the region by constructing a cost-efficient and low-impact archaeological park. We accomplished this with a modest grant from the Fulbright Program’s Ambassador’s Grants. The park consists of a large introductory sign, four smaller ones, and a system of well-defined trails. We also fenced the site off and put in a gate at the entrance. Later, construction of a small museum for the region’s archaeology began nearby with the assistance of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, but there were no funds to complete it.

To deliver our educational message, in addition to trails with informational signs we produced brochures in both English and Arabic, explaining the site’s significance and the potential impact of visitors. This resulted in only minor modifications to the site. The trails, for example, were based on those that we used for daily access. These are essentially self-guided tours, although local Bedouin groups often taken give informal tours of Ghwair I. Thus, some degree of community outreach was achieved with the local Bedouins in the area, but nothing official was undertaken.

In an ideal world, an archaeological park at Ghwair I would be part of a larger archaeological district for the entire Wadi Faynan system, a concept that is currently being considered. But this remains an ambitious concept, and we undertook the Ghwair I park on an informal basis with limited support.

How successful was this? We believe that with the limited resources available, some degree of educational and outreach value was reached. Yet, in the almost ten years since the park was established, there has been obvious deterioration. In particular, the signs have not survived both the harsh climate and vandalism, and the entrance gate has been destroyed. The intended museum presently stands as an empty shell.

Despite this, Ghwair I continues to be visited by relatively large numbers of tourists, and we are confident that they are satisfied with their experience. While there is no formal mechanism for counting the numbers, based on discussions with local Bedouin we estimate that during moderate weather seasons (e.g., March, April) there are hundreds of visitors.

Could we have done more? Of course. Proposals to develop an International Ecotourism Standard include three distinct sub-sectors: accommodations, tours, and attractions, all of which feed into the local economy. How could these be incorporated into the Wadi Faynan?

Should tourists go on self-guided tours to be accompanied by local guides? Yet another issue is overnight accommodations. What about restaurants, gift shops, and toilets? These are critical to a balance between maintaining a pristine natural condition and providing minimal amenities. A nearby former geological survey camp that served as our quite primitive field camp has already been converted to a relatively elegant tourist hotel. Also possible are modest, but comfortable, accommodations in tents.

NEA Figure 12: Luxury accommodations at a former Geological Survey camp near Ghwair I. Photograph by A. Simmons.

The site’s relationships with the adjacent Dana Nature Reserve, and a planned Neolithic trails system have also not been articulated within the Wadi Faynan. Finally, what can one do about vandalism? This clearly is an educational issue that needs to be confronted. Certainly there has been vandalism at Ghwair I.

The concept of an archaeological park is a good idea, but who pays for it? US analogies are of limited use since most parks are paid for and maintained by either the federal or state governments. In Jordan, such resources are much more limited. This has become even more critical in the present political context of the Middle East, which has drastically reduced tourism in Jordan. Without outside tourism, it is unlikely that overstretched government agencies will be willing to increase funding for tourist attractions.

Funding possibilities to consider include the World Bank or the European Union, private sources; requiring projects to incorporate costs into already stressed budgets, some type of government-supported work force, or matching funds, either in cash or in-kind services. We must face reality. Money will always be a very real problem. Our experience attempting to obtain funding through “traditional” funding agencies has been less than successful despite the Ambassador’s Grant award.

To indicate the problems with preservation funding, here are anonymous reviewer comments on a proposal that we submitted some years ago to a major US government agency. This proposal called for research and for funding an archaeological park along the lines discussed here, but on a more ambitious scale.

Comments included that “boosting the local economy is not a [US agency] goal,” that “plans for developing the archaeological park… should not be the responsibility of archaeologists,” and that “until excavation is actually completed it seems premature to be developing plans for potential visitors.” Another reader stated “An archaeological park is a commendable undertaking but I am not convinced that this is a good use of funds. In my opinion, this money would be better spent excavating, and publishing the results, rather than constructing a park.”

Perhaps most amazing comment was “The goal of providing local employment is commendable but should not be the responsibility of archaeologists. The goal of site preservation by means of an archaeological park is highly dubious…. If the excavators are serious about site preservation they should carefully backfill the site and not give out its precise location to anyone” since “Such tactics are standard in American archaeology.”

Agencies operate under severe funding constraints and many of these comments have validity. However, many of them were disheartening, especially from archaeologists. There is more than a little colonial attitude apparent, and many seem to feel that it is not archaeologists’ responsibility, practically or ethically, for educational promotion beyond the limited scope of pure academic research. Such attitudes are paternalistic and arrogant.

It is our obligation to share findings with the public. We have tried to do this at Ghwair I. The Wadi Faynan is well suited for sustainable ecotourism development that will protect the cultural resources and benefit indigenous peoples. Another example is at nearby Beidha, where reconstruction of Neolithic structures is coupled with signage and simple trails to the site. This was accomplished at a relatively low cost and could be a model for future studies.

Archaeological remains belong to all of humanity that demands protection and local community involvement. While careful and proper excavation and publication remain primary goals for archaeologists, preservation, public education, and outreach should be considered equally important. This will require a radical retooling of the discipline in the twenty-first century.

Alan H. Simmons is Distinguished Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas.

From 1988 to, Mohammad Najjar was director of archaeological surveys and excavations for the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. Inhe founded Jordan’s Landscape Tours, which specializes in ecotourism and archaeological study tours.

For more information check out:

- Blazing a Trail at Dana Nature Reserve, Jordan

- Dana Biosphere Reserve in Jordan is an eco-tourism oasis in the desert

If you liked this article please sign up to receive The Ancient Near East Today via email! It’s our FREE monthly email newsletter. The articles will be delivered straight to your inbox, along with links to news, discoveries, and resources about the Ancient Near East. Just go here to sign up.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

Thank you for mentioning Israel instead of the invented land "Palestine." It shows that the authors are not revisionists but do pay attention to facts not revised fiction.

As per keeping the area safe- please take note that some sites like near Sedona, Arizona do not have "luxury" suites but "lodges" that are basic so the visitor can get an idea of what life was like - and do have the basic necessities of modern day living.